Popular trust in the government — belief in the United States’ foundational institutions and values — has plummeted to historic lows. Lethargy and despair pervade the popular consciousness.

It’s not without reason, though.

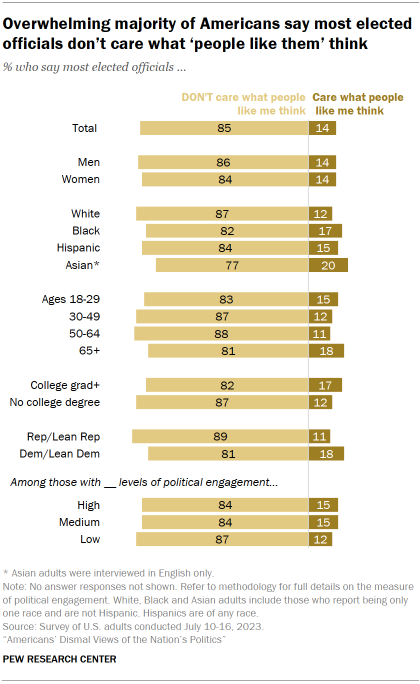

There is a fundamental disconnect in American society between the needs of the people and the actions of the political class.

At the same time, our vision of democracy, a government by and for the people, is boiled down to ticking the red or blue box every two years.

America lacks opportunities for people to actually engage in their own government, as is promised in a democracy, rather than simply remaining a spectator to horse-races. What opportunities we do have, like town halls and ballot measures, are either confined to wealthier portions of the population or unequally available and constantly attacked by self-serving career politicians.

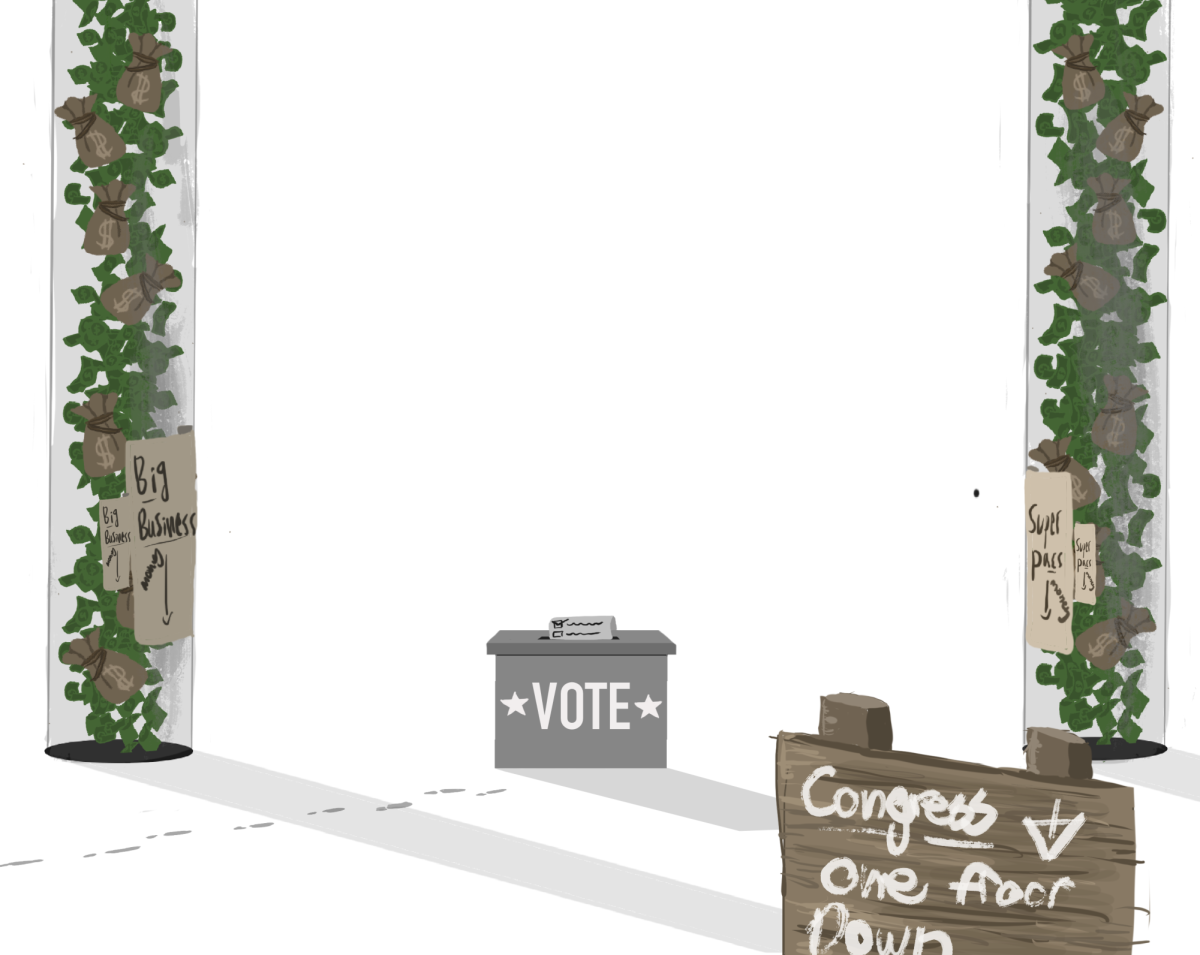

Essentially, the people are locked out of their own government.

It is isolating for democracy to be restricted to biennial voting. It disconnects people from the actions of their representatives and is indicative of a government that is guided not by our voices, but the voices of unaccountable representatives beholden to the interests of their wealthy donors.

All of this makes politics — deciding who gets food, who gets housing, who gets regulation, and how we are going to stumble together toward our future — a far-away sphere, beyond the reach of ordinary people.

Our engagement is limited to yelling at our relatives, rather than a vibrant aspect of community and daily life.

Political commentators on both sides of the aisle pour resources into national races, focusing on poll numbers and treating politics like a horse track, while many Americans are still disconnected from the local politics that are most closely tied to their own voices.

It makes sense that everyone can name the president, but it would make more sense — and be emblematic of a more healthy democracy — if Americans could also name those directly representing their communities.

Even during those limited windows of November participation, often only a slim majority of the population even takes part, since many people don’t have the ability to take time off to vote or feel their voice actually matters.

States also offer wildly different standards of support for voters, with many not offering mail-in voting or even voter guides to reliably inform people.

This leads to an environment where local races are downplayed, and the actions of local representatives are even more forgotten after an election than on the national level.

How many of us know how our senators vote on topics important to us?

How many ways do we have of holding them accountable for decisions their constituents disagree with?

We have exactly one: the next election, where as often as not voters are dissatisfied with limited and unpleasant options.

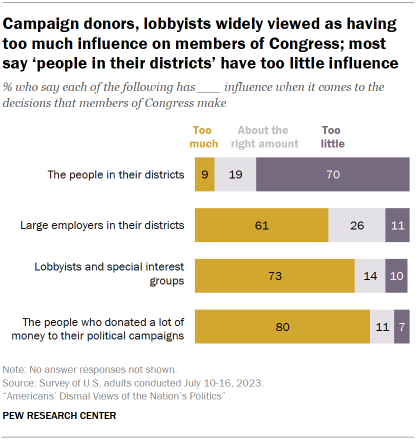

On a national level, it leaves the door wide open for rich donors and business lobbies to shell out huge sums to swing a disconnected electorate. Especially since much of that electorate is more focused on making enough money to live with dignity and are left without resources to understand their own possible decision-space.

This leaves politicians focused on policies which have nothing to do with what is best for the American populace and everything to do with their donors’ profit margins.

Then after the election, we either forget our representatives or we build them up into something they aren’t.

We must remember that in reality, these are all just people.

They scroll social media in long meetings and sleep on the job. Only, in addition to that, they determine who gets bread and who gets unfulfilled hopes for dinner.

They are power-brokers, yes, but they still are fellow flawed humans, not a divorced sphere of idiots or a political commentator’s mythologized heroes and villains.

On the local level, our neighborhoods and communities are simultaneously coming under assault from an age of isolation, one reinforced by the pandemic but built out of an all-consuming social media, internet, and the polarization these exacerbate. Third places — places people frequent to socialize and build relationships outside their work and home, like church, community centers, or even bars — are equally disappearing.

Local journalism, the kind that can form the backbone of a community, help tie people together, and help people understand the world around them, is also dying out.

This withering of community has been as instrumental as anything else in undermining democracy.

People are left disconnected, hopeless, and feeling, justifiably, that they have no voice in their future.

It is extremely hard to consider such a society — one with a limited and disconnected electorate, policy dictated by the wealthiest, and lack of participatory opportunities for anyone, let alone those poor and disenfranchised — to be a democratic one.

To create a democratic society we need to counteract the contraction of civic life and opportunities.

This means engaging with our local politics and representatives, organizing in our communities toward everything from rebuilding third places to canvassing for agreeable candidates, creating mutual aid groups, and supporting local journalism.

To allow the working people of America the ability and resources to civically engage, we need to push for the federal adoption of a national holiday on Election Day, alongside quality, nonpartisan voting guides and resources everywhere.

States need to adopt universal mail-in voting to further universal participation, while also embracing more direct democratic measures like ballot measures, town halls, community forums, and the like.

We need to elect candidates who will initiate a more strenuous crackdown on oligarchical influences in politics by eliminating Super Political Action Committees and other avenues of corruption.

Finally, we cannot forget the role of labor and unions in both community and democracy. Supporting labor in our local communities and programs is crucial, as a strong labor movement means that average people have the power to advocate for themselves against those same oligarchs whose money decides so much in politics.

In this era of enormous disconnect and corruption, fighting for and achieving this democratic revolution is exceedingly difficult. But it is clear that without popular action, there is reason to believe that the people’s voice will keep meaning less and less, and the amount of money oligarchs have to throw around will keep growing.

But we, the students and young people of America, can make this change from the ground up.

It will take dedication, and all of our energy and fervor, but through organization and hard work we can reshape our society even in this time of ever-growing authoritarianism.