Senior Hailey Heytvelt’s commute to volleyball practice is at least 40 minutes long.

On her way to the gym she practices at in Beaverton, Heytvelt takes a route that’s been routine for the last four years: over the Interstate 5 bridge, off Exit 302 B, past OMSI and the Oregon Zoo. As one of seven La Salle students living in Washington, she makes this 80 minute round trip at least three times per week, though her drive to school — over Interstate 205 — is five minutes shorter.

The long length of both these everyday trips is due to traffic, a hurdle presented to anyone crossing between Portland and Vancouver over the Columbia River.

The Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) program could change this. While its goals, and the construction necessary to make them a reality, could have consequences by redirecting commuters from I-5 to Interstate 205, it might also improve the seven to ten hours of congestion that occur during peak travel times through building an additional bridge, creating a transit system, and modernizing the entire five mile corridor, including the seven cramped interchanges that lead to the significant delays.

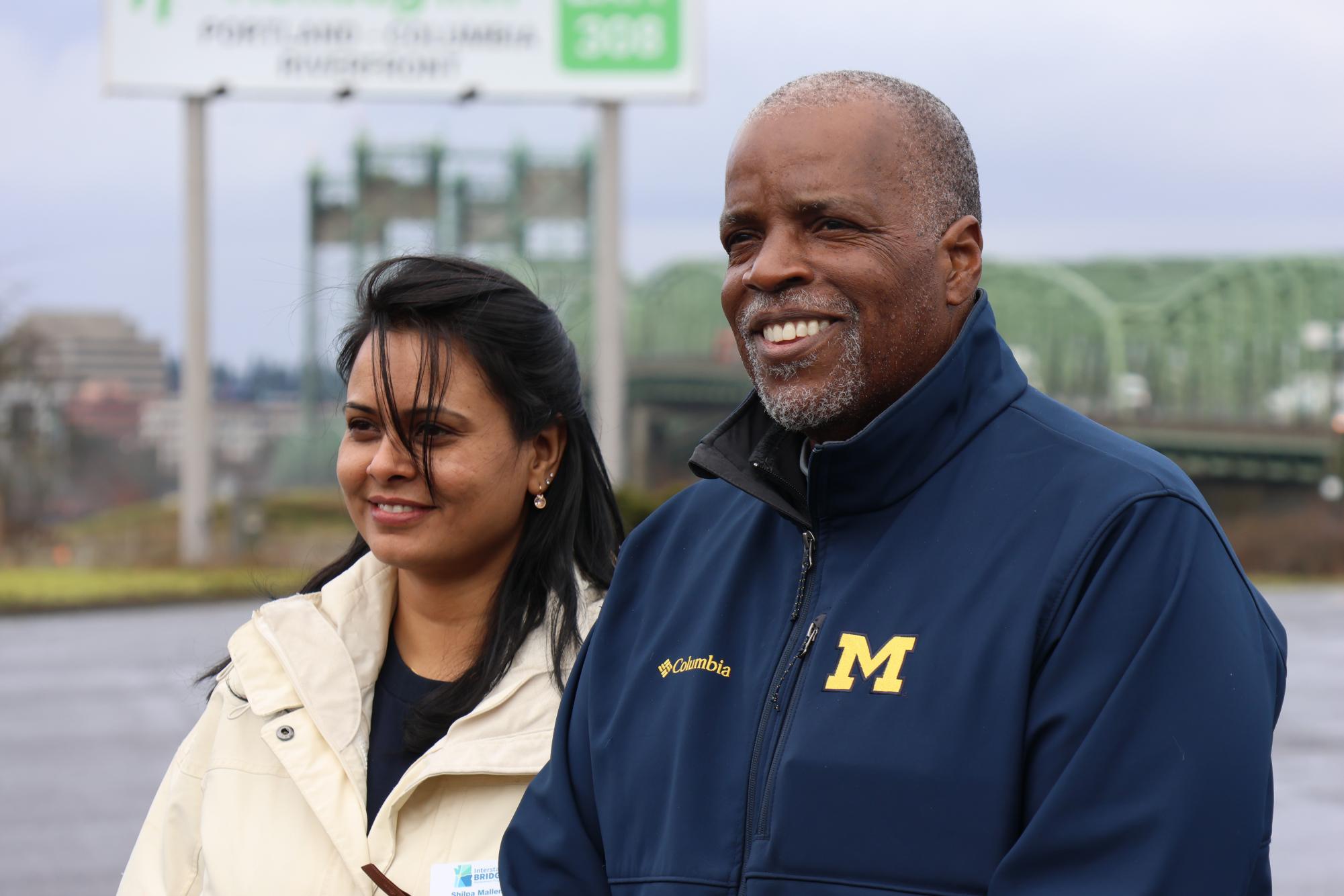

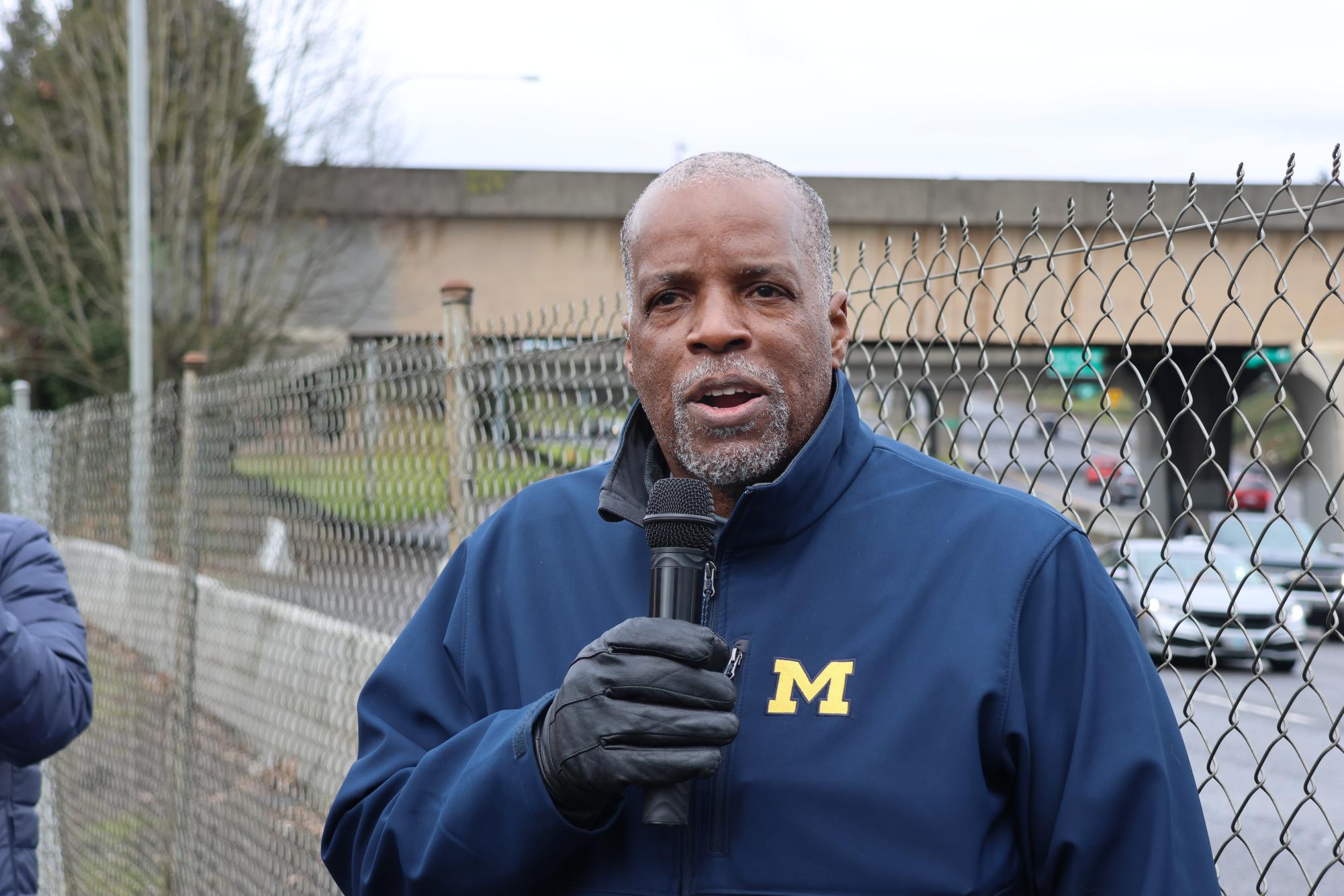

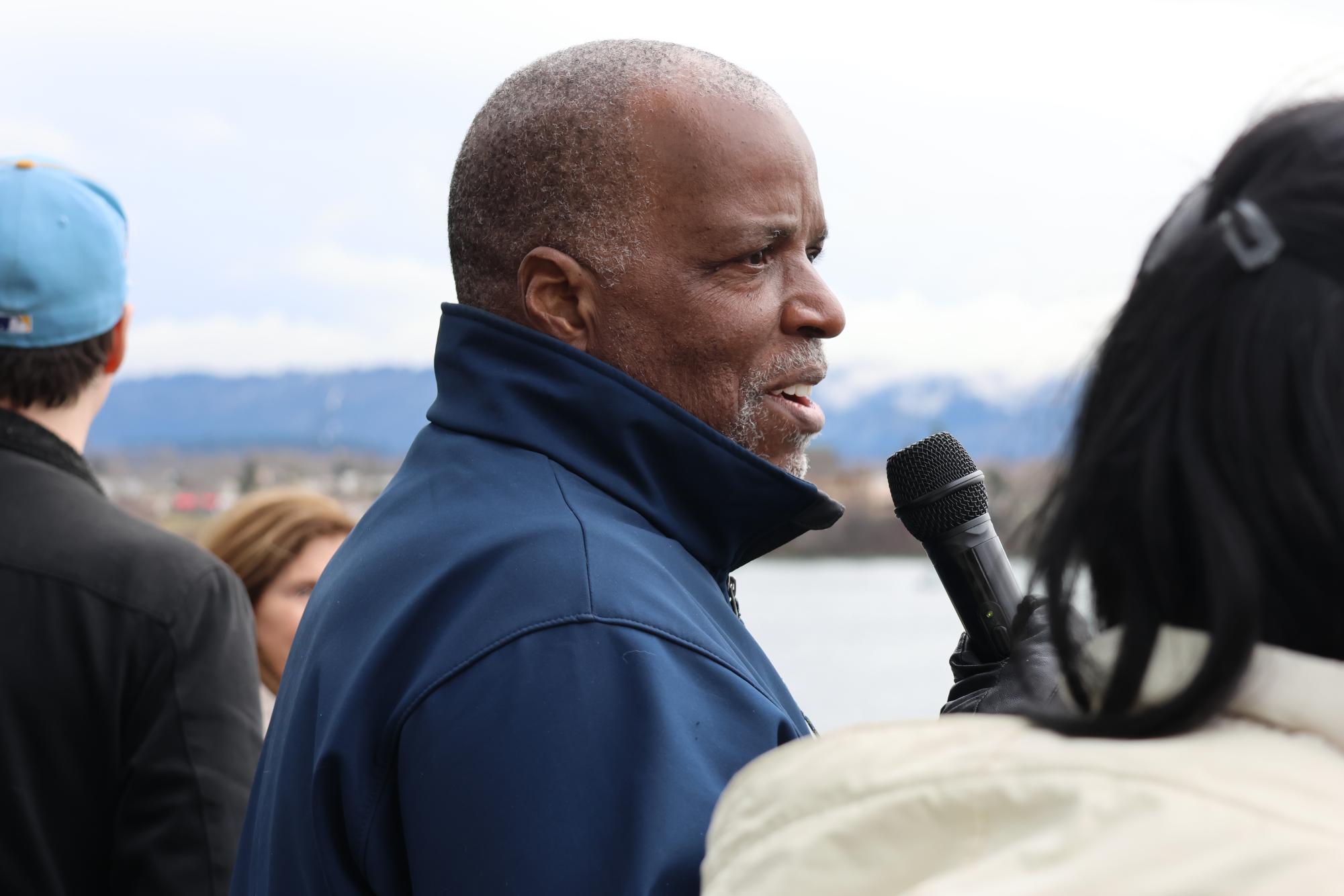

“That’s what’s different about this project,” Program Administrator Gregory C. Johnson said, speaking during a bus tour of the IBR program’s area on Feb. 15. Not only are their goals more comprehensive, but they also are taking a distinct approach, highlighting environmental sustainability and equity. “There are not very many projects that are trying to do the number of things that we are trying to do.”

But the IBR program’s expansive goals for the bridge come with expensive costs.

As of spring 2024, the projected price tag is between $5 and $7.5 billion; so far, the program has been the recipient of a $600 million federal grant, along with pledges from both states to contribute $1 billion. To raise the remaining $3.4 billion necessary for the estimated cost of $6 billion, they are applying for an additional $1.5 billion in federal dollars and plan to install electronic tolls ranging from $1.50 to $3.55.

For sophomore Alexa Storie, time management, along with how the funds will be utilized, are some of her biggest concerns regarding the program.

“If you aren’t on time, it costs more money,” Storie said. “That’s taxpayers’ money.”

According to Johnson, one of the largest criticisms the program faces is that the “major” amount of federal spending being poured into it funnels money away from other critical state projects. However, Johnson said, if this bridge fails, rippling consequences for the region would follow, such as gridlock and “the economy grind[ing] to a halt.”

“Everyone is fighting for dollars, whether it’s schools, whether it’s policing, whether it’s homeless issues — everyone needs dollars,” Johnson said. “But, once again, in order to have a functioning economy, you need to have a transportation system that works.”

Currently, he says, this bridge doesn’t.

“Bridges are made to last,” Johnson said, mentioning how the I-5 bridge turned 107 years old on Feb. 14. “But these bridges are considered functionally obsolete, which means that they no longer serve the modern economy, [or the] modern needs of a growing area.”

Oregon and Washington, along with most of the Pacific Northwest, are located on the Cascadia subduction zone, a tectonic fault line stretching from Canada’s Vancouver Island to Northern California capable of producing 9.0 and higher magnitude earthquakes. According to Design Manager Shilpa Mallem, this makes the bridge’s seismic vulnerability a major concern.

As the bridge is also one of the largest freight corridors in the country, connecting all of the West Coast — from Washington to San Diego — it is “tremendously important for national and international trade,” Johnson said, meaning that its collapse would provide obstacles not just for commuters, but freight trucks transporting goods.

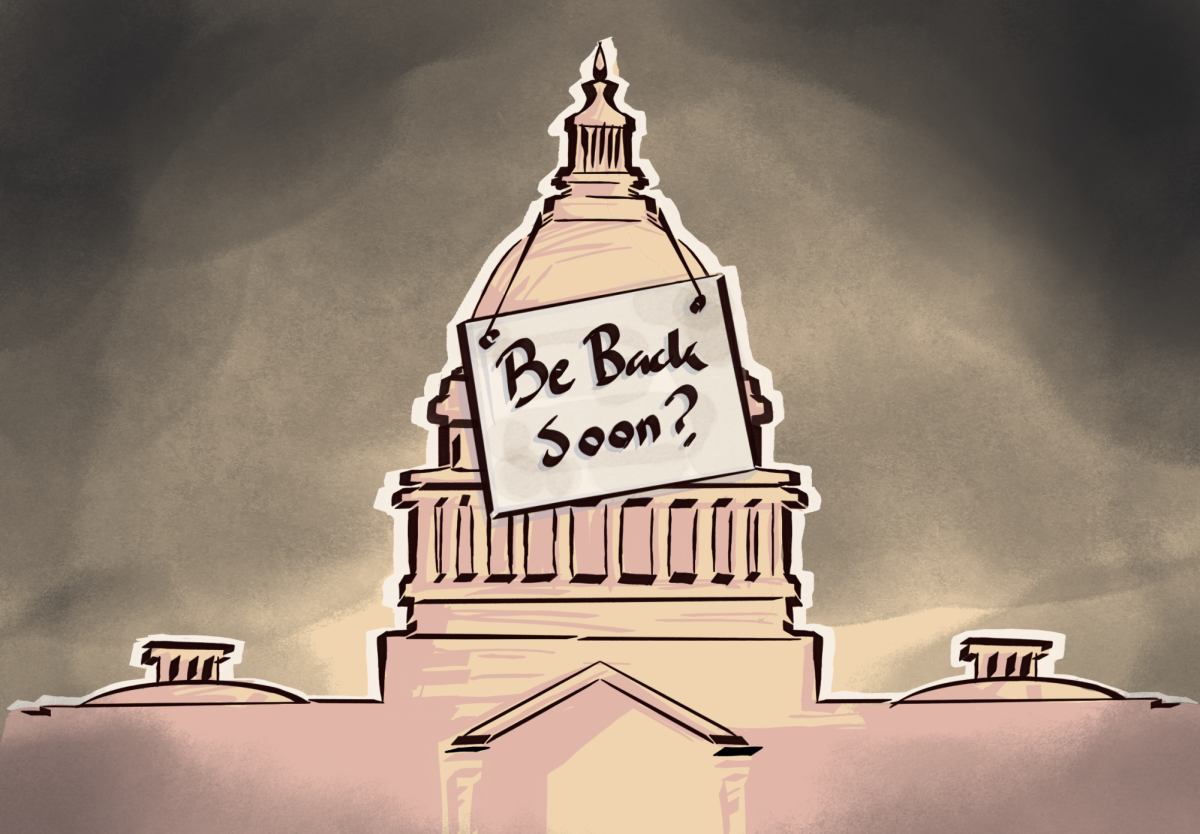

The IBR program is the second attempt by both Oregon and Washington’s governments to restore the Interstate Bridge. The previous, called the Columbia River Crossing (CRC), ran from 2004 to 2013, and ultimately lost funding at “the 99th step,” according to Johnson, suspending the program for another seven to eight years.

“Time is not the friend of a major, major construction project,” Johnson said, referencing rising inflation rates and material escalation as consequences that come with delay. As he pointed out, when the CRC was working to modernize the bridge, the approximate cost was $3.2 billion. It’s more than doubled since.

Time is money, and Storie, who also lives in Washington, said that she hopes the project will consider how they affect people’s day to day lives.

“It takes a lot of time to just go to work, to wake up, maybe get your kids ready,” she said. According to Storie, the majority of travel time comes from the congestion over I-5, and so she hopes the program will factor in both how they can improve that issue, but also how construction and the transferring of some traffic to I-205, where her daily commute takes place, will shape her life.

Once it starts, construction will last for around ten years, creating approximately 18,700 person-year jobs directly involved with building the bridge.

Right now, the program is undergoing environmental evaluation, and to meet their start time for construction — or in-water work date — in September of 2026 they must complete a number of milestones, such as continued funding and grant applications, permitting, pre-construction, and approval from the Army Corps Navigation Channel.

Construction in the Columbia River is only authorized from September to February due to the seasonal salmon runs, so missing this window will set the project back by a year.

“A year, yeah, you’ve been doing this for 25 years — what’s another year?” Johnson said. “But another year on the back end of construction will cost us $300 million just in inflation and escalations.”

The IBR program intends to “get this across the finish line,” Johnson said. Presently, they are working through a mandatory federal process, called the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and assessing the risks posed by the project to the environment of the Columbia River. These liabilities include those impacting air quality, wetland habitats, noise level, property, and endangered species.

But, according to Mallem, the program hopes that in some areas, it can reduce the repercussions that the Interstate Bridge leaves on the environment.

For example, the current bridge’s design funnels rainwater directly off of it into the Columbia, bringing along microplastics from car tires, chemicals, oils, and heavy metals. Mallem said that the program’s goal is to propose a plan where water is collected before it enters the river and then treated off site, so that when it does go into the Columbia, it’s not transporting harmful residue with it into the ecosystem.

Johnson said that understanding and mitigating how the bridge negatively impacts the environment, through both pollution and emissions, remains one of their biggest priorities.

“We know that transportation is one of the largest generators of greenhouse gasses,” Johnson said. “Commitment to multimodal travel is how we are hopefully going to, once again, make this a greener and better project.”

According to chemistry teacher and Science Department Chair Mr. Matthew Owen, unless people commuting between Portland and Vancouver are carpooling, the lack of public transportation options individualizes their carbon footprints, rather than there being clear opportunities and incentives for them to use cleaner methods of travel. According to Heytvelt, a bus lane — such as the one on I-205’s bridge — and safer sidewalks should be implemented to address this issue.

“People who are crossing over from Vancouver on a daily basis, or a semi-weekly basis, only have one option,” Mr. Owen said. “I do think it’s a concern that it encourages more transportation by car.”

A standard passenger vehicle emits around 4.6 metric tons of CO2 annually, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. With around 140,000 vehicles traveling across the I-5 bridge every day, a direct way that the program could significantly reduce how the bridge contributes to climate change is to provide alternate forms of transit, such as light rail.

“When we think about our own carbon footprint, one of the largest pieces of it comes down to transportation,” Mr. Owen said, explaining that building further options for environmentally friendly travel encourages people to utilize methods aside from single-passenger vehicles. “Greener options will provide a way for individuals to lower carbon footprint,” he said.

One of the options that the IBR program is considering involves a light rail system from Portland to Vancouver, extending TriMet’s yellow line from the Expo center across state boundaries. In addition to this, the program plans to build facilities (like stopping points along the walkway where people could appreciate the views of Mt. Hood) that make the bike and walk paths more accessible and “inviting,” which, according to Johnson, they currently are not.

“I refuse to ride my bike across there, and I’ve been biking for years,” Johnson said, expressing that he avoids the somewhat unsafe walkway currently in place. “It’s so narrow.”

The program aims to make bike and public transit both reliable and cost competitive to transition people he said are “married to car culture” to a more environmentally sustainable form of travel. But as Johnson pointed out, according to a poll conducted by the IBR program, there’s already a major demographic invested in these types of transportation: young people.

Not only does the program want youth to engage with the potential transit system, but they also hope for them to learn about what is happening in order to provide input on it.

Constructive criticism will be encouraged, particularly during the “crucial period” after the publication of the Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS). As part of NEPA’s mandated process, this 1,000 page, searchable document compares analysis of key foundational design elements along with a no-build alternative, and will be followed by a 60 day public comment period.

“Feedback is key in this situation,” Heytvelt said — not only that of students, but also the people living in North Portland or Vancouver, whose lives the replacement program will impact the most. “I think it would be very important to hear not only other workers’ opinions that are helping with improving or remodeling the bridge, but the… people [who] cross it every single day.”

Considering that the draft will be detailing the project’s impacts on both the community and environment, Johnson encouraged young people especially — as the ones who will have the new bridge for the majority of their lives — to submit comments online, attend public hearings, send emails, or call the IBR program’s hotline with their thoughts.

“This is important for us and important for our team, to engage with youth. [It] is important to have your voices heard,” Johnson said. “You don’t want to be 70 years old and someone says, ‘well, why didn’t you tell them to do this?’ You want to be 70 years old, tell them ‘hey, I had a part in helping shape what that bridge looks like.’”

Both the bus tour and a virtual press conference held on Feb. 20 were part of the program’s commitment to equity. In addition to people with disabilities, the elderly (age 65 and over), low income households, people with limited English proficiency, individuals or families experiencing homelessness, and Black, Indigenous, and people of color, the program has identified young people (age 25 and under) as an equity priority community, or a group often “left out of projects like this,” Johnson said.

Between these groups, “it’s not so much as a competition of who gets hurt the most,” Community Engagement Lead Salomé Chimuku said. “It’s how do we mitigate, [if] not avoid harm completely to those communities, who tend to be the ones who bear the brunt of these programs and these projects.”

With both an equity advisory group and a chief equity officer, the program hopes to avoid the mindset employed by previous Departments of Transportation (DOTs), Johnson said.

According to him, traditionally — or at least when the Interstate bridges were built, in 1917 and 1975 — the environment and the people living there weren’t considered. By giving micro grants to “different entities” within the community to ensure that people who speak English as a second language or with limited proficiency have their viewpoints heard, and through working with ten federally recognized tribes and the National Parks Service, the program hopes to minimize the consequences those previous practices had, Johnson said.

“We are now trying to change that dynamic, bring different voices to the table and bring different perspectives so we are building things that are acceptable to the communities that we are building those things in, ” Johnson said. “We want to make sure we are casting a wide net to get everybody involved and have their voices heard in this.”

Johnson brings personal experience and understanding with him when considering the impact the bridge will have.

When he was four years old, living in Northern Detroit, the predecessor to the Michigan DOT used eminent domain to seize his home and build a new roadway. While he was excited at the opportunity to live with grandparents, his father viewed it differently.

“I thought it was fun. But my father — and this was back in 1964 — he didn’t think so,” Johnson said. “He thought that he was not treated fairly by the highway department. He felt that he did not get fair compensation for his house.”

According to Johnson, his father repeatedly told him that story from when he was young enough to understand it to one of their last conversations, and it altered the way he approaches his work. As Chimuku said, it shows that there can be many different impacts to people’s lives from construction — tangible, but also intangible, emotional, or generational.

“When I build infrastructure, or when I am involved in infrastructure, I take that sensibility to what I do to make sure that nobody feels that their voice hasn’t been heard,” Johnson said.

The property impact is one area that will be addressed in the Draft SEIS, and while there will be people unhappy with losing a home or business, Johnson said that the program wants to guarantee fair compensation and understanding of the process, so that no one feels that they weren’t taken into consideration. Compensation itself is calculated through the fair market value by hired appraisers, and includes relocating businesses elsewhere or offering relocation packages to homeowners.

“This is complex. It is extremely emotional,” Johnson said. “I’ve sat in folks’ living rooms and houses, that you may not think have much value — they have tremendous sentimental value for people. So they must be treated with dignity and respect… that is what we try and do.”

Eminent domain is their last resort. It can be used to compel someone who doesn’t want to move to do so, and since “it has been done in ugly ways in this country,” as Johnson said, it’s not something the program invokes readily.

“We are trying to make the best project that meets the needs of this region going into the future,” Johnson said. “Because this bridge — what we build — will be here for the next 100 years.”

Farryn • Oct 31, 2024 at 5:31 pm

I love The Falconer