What does it mean to be creative? What qualifies as artistic intellectual property? Why is art important? What does the creation of art add to the lives of artists and the rest of the world?

And how do the answers to these questions change when machines can create art?

This is what society has been left to wrestle with since the release of increasingly more capable — and even exemplary — AI art tools, such as Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and DALL-E, to name a few. The billions of images they have generated since release, most based on text prompts and produced in seconds, show how revolutionary this technology is, both for the art world, machine learning, and society as a whole.

Yet these questions, which continue to develop alongside AI tools, complicate things. While the ability to quickly generate high-resolution images with short text instructions is nothing short of “amazing,” as La Salle art teacher Ms. Cha Asokan put it, senior and AP Studio Art student Asher Wolf pointed out that it can become, when overused, “a crutch that will stop you from actually developing those skills.”

Easy to access AI systems such as DALL-E or Midjourney open a lot of doors, Wolf said, both for cool new art that couldn’t be created in the past and for people who aren’t artistically talented to produce beautiful images. But in doing so, it removes what he and Ms. Cha said the most crucial part of art is: the process.

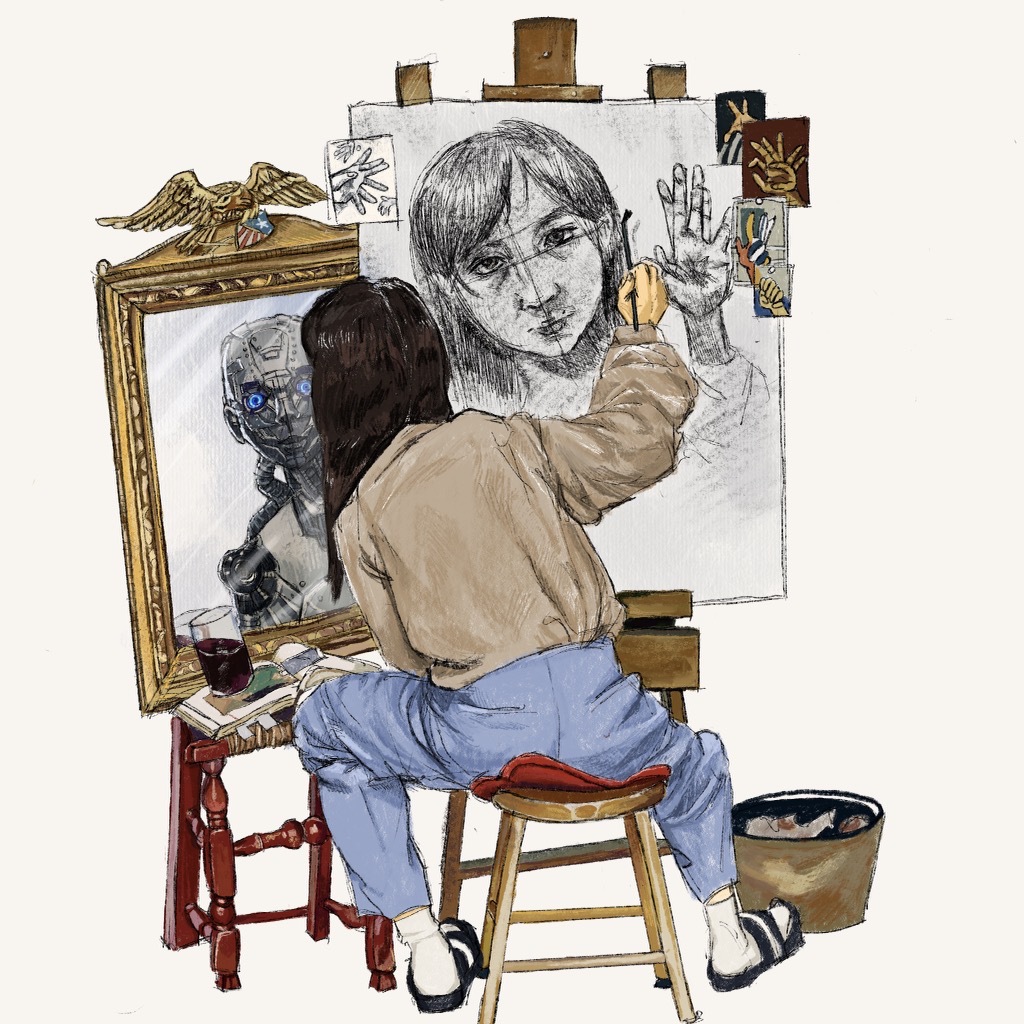

“More important than the final product that you get [is] the process that you go through,” Ms. Cha said. When generating art through text-to-image AI tools, you’re providing the prompts and directions, but you’re not going through the process of trial and error that she said comes with creating an idea that’s yours. According to Wolf, the majority of what being an artist is lies in that process. Artists spend the most amount of time with the unfinished piece, expressing their ideas and thoughts in a process that leaves the completed artwork “a very small part of the journey,” Wolf said.

“The point isn’t to have this finished piece,” Wolf said. “It’s to develop these skills and to put the work in over the time.” In focusing on the visual finished piece rather than the skill, time, effort, and care that it takes a person to create it, AI art tools eliminate what he said is “the most beautiful part” of art.

While he’s heard people say that AI tools are allowing those who can’t paint or draw to have the joy of creating art, Wolf disagrees with this viewpoint. According to him, AI lets people attach visuals to their ideas, but what they don’t do is help the person generating those visuals develop skills or enjoy the many benefits of artistic creativity. It’s an outlet that can be used to process life, he said, or discuss important issues such as mental health, as putting your ideas into something and having an end result that expresses your emotions is incredibly valuable when grappling with significant or complicated topics.

If someone wins an art competition with an AI art piece — beating handmade or digitally created artwork from artists who have gone through the process, who have put themselves into it, as Ms. Cha encourages her students to do — she asks the question of whether or not “they deserve it.” Are they the artist if all they provided was a prompt? As Wolf observed, regardless of the medium, talented art is hard to make. Usually, the skill, time, and care that has gone into creating it reflects the piece. But with AI art, anyone can type in a few words and generate an image that would have taken an artist 10 to 20 hours to make.

“If you get rid of that process, and it’s just [the] idea to [the] finished piece … it’s hard to say, are they still an artist?” Wolf said. “If they don’t have to go through the process of making their idea into reality, then what are they really doing?”

Aside from side-stepping the most crucial component of creating art, AI tools directly impact artists, and, as junior Jadzia Marsh said, while it can be a positive and “important tool,” it also comes with the potential to disrupt and supplant their careers entirely.

The majority of AI art tools today are generative models, meaning that they learn patterns from given datasets and create new content based on what they’ve learned. In order to train tools such as DALL-E, Open AI — the company responsible for creating DALL-E along with Chat GPT — used large collections of image-text pairs. The majority of these images were used without artists’ consent or permission. In response to this, many, such as illustrator Michelle Jing Chan, have argued for stricter regulation around how art is used to train AI algorithms, so that the rights and properties of artists are protected, considering that the technology using their work as source material also provides consumers an avenue to replace them.

While the use of artists and their art, shown in the recently leaked list of 4,700 unconsenting artists who have allegedly been used to train Midjourney, is in unclear legal territory, multiple lawsuits surrounding the issue have been filed. The stock photo provider Getty Images, along with illustrators Sarah Anderson, Kelly McKernan, Karla Ortiz, and many others, have sued a variety of AI art companies, such as Stability AI and Midjourney, over alleged copyright violations in the companies’ usage of their work to train AI algorithms.

Allegations that Stability AI utilized copyrighted images to create Stable Diffusion have been denied by the company, along with the claim that it stored and incorporated these artworks into its AI system. Furthermore, the company argues that the training of its model doesn’t include outright copying of artistic works. Rather, it involves the development of parameters — such as color, shape, composition, and other attributes — from images for the software’s output, something AI companies have consistently defended as an acceptable fair use exception to copyright law.

Marsh’s opinion is that “anytime an AI uses that specific artwork to make something else, the artist should get a small commission price,” ensuring that AI companies can work with artists instead of in competition with them. But, regardless of what people think the solution should be or how and if artists should be compensated, she said that it needs to be discussed, “because it can’t be an issue that’s just swept under the rug, or else it’ll just keep escalating.”

Another problem, as Marsh pointed out, is that people who dislike specific artists or their commission prices have begun to prompt AIs to mimic their artstyle, undermining that artist and their work.

“That artist probably spent years, like I have, developing a style only for it to be taken and used as a training tool to make something else that maybe took an hour,” Marsh said. “It took someone so long to make it and an AI one second to take it and learn from it.”

Ms. Cha said that although the more business-focused art professions (such as graphic or interior designers) are definitely going to be affected, artists who are able to embrace it as a tool won’t see their jobs disappear. The key to doing that — to embrace and grow from AI instead of being scared of it — is, according to her, to approach it with “less fear and more understanding.”

“Art is going to be completely altered,” Ms. Cha said, referencing previous revolutionary artistic tools like photocopiers and cameras as examples of the kind of change AI art will cause to happen. But those tools have, if anything, helped art advance. As Wolf pointed out, the way AI art changes artistic trends might mirror the period of time after photography was invented: art shifted from a focus on realism, capturing the moments of life as best as possible when nothing else could, to a surrealist movement that illustrated the abstract ideas a photo could not.

“It’s going to change things, but it’s not going to end anything,” Ms. Cha said, explaining that while both have a unique purpose, a clear difference exists between 3D printing and her students making porcelain jewelry. That difference isn’t going away because the 3D printer (or AI art) is becoming more skilled. “That human component is what makes art special,” she said. “It’s what makes it important to not only artists, but the viewer and the audience.”

There’s a value to visual art beyond just being a beautiful image, and Wolf hopes people will realize that, along with the difference between what a human creates and what AI can make. “The really beautiful art that ends up in museums and makes these artists super famous is the art that has a really deep meaning or a personal connection,” Wolf said. “That’s when art becomes something cooler than just a nice thing to look at.” Sometimes, he said, people can see modern art and assume that they could do the same thing, without appreciating the depth of thought that has gone into it.

Ms. Cha admitted to doing this herself, in regards to Mark Rothko paintings. While he’s now one of her favorite painters, she originally saw them and thought ‘this is dumb. This is just blocks of color; anyone could do this.’ But once she stood in front of them, it was an entirely different experience, as Ms. Cha connected with the paintings in a way that she described as almost spiritual. “I don’t think AI could ever do that,” she said. “There’s no way AI could capture whatever magical thing he was doing in those paintings.”

“Art isn’t just about, ‘oh, I made this thing,’” Ms. Cha said. For example, if you’re an interior designer, according to her, your job is more than just making a nice room — it’s meeting with people, connecting with them, and understanding their philosophy in order to design a space that reflects who they are.

“Huge books don’t get written about artists because they made pretty paintings,” Ms. Cha said, “It’s because [they] lived a life that was influential and important. So, that’s not gonna be taken by AI … it can’t be.”

While Wolf pointed out that AI should not be overused, Ms. Cha is hoping to strike a balance, utilizing it as a tool to support but not circumvent the artistic process. When her students create art projects, particularly social justice projects, she has them go through what she calls “almost an academic research process” along with planning in their sketchbooks so that they can show they’ve thought it through. She said that AI can help with that research.

“If it can expand the idea, then go for it,” Ms. Cha said. If AI could help a student organize something compositionally, or if, as Marsh suggested, it could be used for conceptualizing ideas or as a resource to get inspired, Ms. Cha supports that. “Just show it and give credit,” she said.

“The feeling of something handmade versus bought from Target is absolutely different. And that’s kind of AI,” Ms. Cha said, explaining that, to her, the difference between AI-generated art and what artists create mirrors that of holding a five dollar store-bought coffee mug versus one handmade by an artist.

“Do you want the Target mug, or do you want the one that makes you feel something?” Ms. Cha said. “The one that connects to you as a human?”

JP Murrell • Jan 24, 2024 at 8:34 pm

What an insightful article that explores the legal, ethical, and personal facets of the use of AI to create art. AI in all its various incarnations is forever part of the creative space. How it is regulated, developed, and used will have a definitive impact on the creators of art from competing with AI created works to their livelihood as content creators.