Chatting About Chatbots: La Salle Responds to A.I.

With the rise in accessibility of A.I. and chatbots, La Salle has been forced to navigate the blurred lines of helpful versus destructive uses of A.I. in an academic setting.

May 17, 2023

Beginning with ChatGPT’s sudden launch late last year and the subsequent fascination with A.I. that OpenAI’s large language model spurred, talks around A.I. and the floodgates it has seemingly opened in the world of education have entered schools across the country, including La Salle.

On April 20, Vice Principal for Student Life Mr. Aaron Hollingshead attended a meeting regarding A.I. use in school, where he was able to meet with administrators from other Catholic schools in the area to discuss their thoughts on A.I. and policies surrounding it.

“It brought to my attention that pretty much all the schools in our network are thinking about and talking a lot about A.I.,” Mr. Hollingshead said.

In particular, the newfound accessibility of A.I. chatbot programs has raised many questions for the La Salle community, especially when considering academic integrity and the future of A.I.’s place in the classroom.

“As a staff, we are starting to really dive into how it’s going to revolutionize education and what that means for us on a day-to-day execution of lessons, assessments, etc.,” Vice Principal for Academics Ms. Kathleen Coughran said.

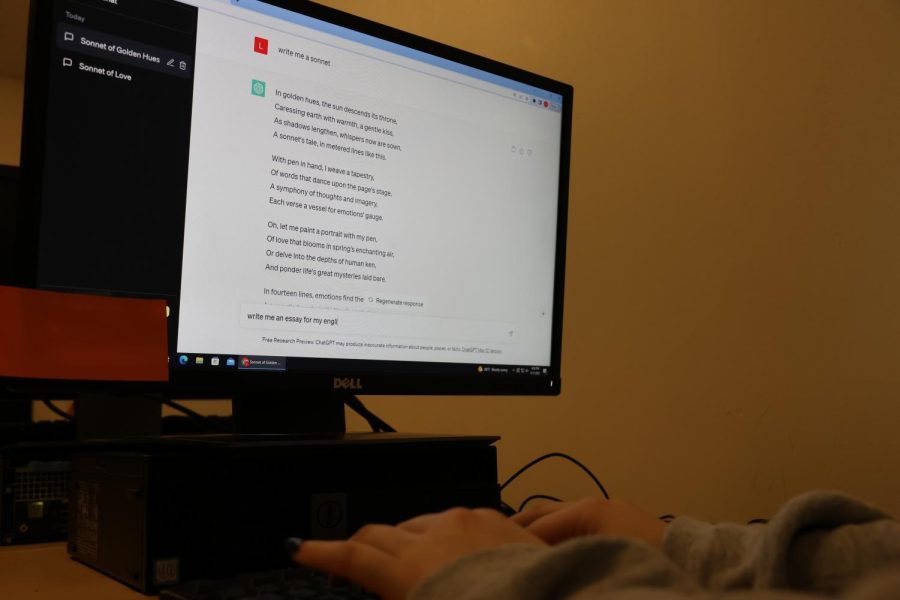

With large language model A.I. programs capable of producing written responses — which can range from a couple of sentences to long-form essays when prompted — within seconds of entering a specific question or command for the A.I. to carry out, educators across the country have identified both risks and benefits that these programs pose when students have access to them.

“I think it has a lot of really, really, really amazing possibilities,” math teacher Mr. Chris Cozzoli said.

However, despite seeing the ways in which A.I. has been helpful to both him and his students — by using ChatGPT to create assignments and assessments and seeing his students use A.I. programs as math tutors — his primary concern with students using A.I. is that they’ll utilize it to do their work for them, rather than work to understand material in order to produce their own answers.

“We’re going to be dealing with the same kind of pitfalls that alternate technology has had in the classroom, where without proper instruction and scaffolding and support,” Mr. Cozzoli said, “students are going to be misusing it and using that to create shortcuts and cheat without engaging the material deeply.”

In response to A.I.’s sudden arrival into the world of education and finding that students on campus have already begun using it to do their schoolwork, La Salle has taken an approach not dissimilar to already existing policies around practices of academic honesty.

According to Ms. Coughran, language drafted by principal Ms. Alanna O’Brien that was shared with La Salle’s staff outlined that students are to only use A.I. under explicit teacher direction and with proper citation — a protocol in alignment with the official plagiarism policy included in the Student Handbook.

The new policy also states that students submitting work created by A.I. without proper credit will be subject to disciplinary action, and students unwilling to follow the policy could face suspension or dismissal.

“What we want to do is make sure that they’re employing critical thinking around the use of A.I.,” Ms. Coughran said.

And, according to Mr. Hollingshead, action on this front is already underway, including having conversations with teachers about inserting the language around student A.I. use in next year’s course syllabi, as well as officially incorporating it into the Student Handbook for next school year, and also possibly sending teachers to training sessions about A.I.

With the official policy in the works to be finalized by the next academic year, both Ms. Coughran and Mr. Hollingshead emphasized that the language will likely be reviewed and revised alongside the quick advancements of A.I. and that “it’ll evolve, it’ll be a living thing,” Mr. Hollingshead said.

Among La Salle’s community, many hold mixed feelings toward the idea of A.I. in general, particularly its use in learning environments, with some being almost entirely opposed to the idea and others expressing openness to it or a range of positive and negative thoughts.

For senior Eli Struyk-Bonn, his opinions on A.I. remain primarily in the realm of opposition. “I’m not really the biggest fan because I’m an artist,” Struyk-Bonn said, explaining that seeing A.I.-generated art submitted to art competitions is disappointing to him because of the lack of human effort he sees in that specific process and because “it takes away all the value I find in art.”

However, other students said that they think A.I. has both helpful and harmful aspects.

“I think [chatbots] have times and places, and I think that the more people try to deem them all bad or all good, the more problems we’re going to have,” sophomore Avari Brocker said. “We need to recognize that A.I. is a gray area.”

While Brocker discouraged the use of A.I. for students in doing their schoolwork, she explained that using the technology for medical purposes would be an example of when she would be on board with using A.I.

Agreeing with Brocker, sophomore Rowan Bienapfl expressed a similar sentiment towards A.I., stating that there can be both positive and negative uses.

“I think it’s something that’s very advanced, and I think it’s time that we should continue to nurture and grow and educate people for medical purposes and other technological advancements in general,” Bienapfl said. “But, I feel like it can be easily abused, and there needs to be some type of restriction, and not everyone should have access to it.”

For some staff, particularly those teaching subjects that involve primarily written responses, like English, accepting that A.I. has been made largely accessible to their students is something they are continuing to grapple with.

“I think my concern around [A.I. tools], from an English standpoint, is students choosing to use them instead of doing the thinking themselves,” English department chair and teacher Mr. Paul Dreisbach said. “But I also recognize that there are disciplines that they’re really heavily useful for. … I suspect that it’s sort of something we’re just going to have to kind of accept and try to work with.”

According to Mr. Dreisbach, talks of using A.I. detection programs to check students’ work has been limited to conversations solely among department staff members. However, false positive identification of A.I. is a concern, with teachers worrying that a student could be accused of turning in A.I.-generated work when it was really their own.

In the meantime, some teachers have simply used other methods to identify the use of A.I. in student work.

“In the way we write, the way we use language, is quite unique. It’s like a fingerprint, and every student that I have has his or her own fingerprint,” English teacher Mr. Chris Krantz said. “If I’ve read enough of your writing, I know your voice, I know how you write, I know how you sound, so the best tool I have right now is my close reading of student work to see if what you’ve written sounds like you because the machine won’t be able to — yet — approximate your voice.”

Mr. Dreisbach also echoed that same sentiment, saying that although the writing that chatbots produce can be very insightful, there is no personality behind the words. “It doesn’t really have that heartbeat,” he said.

Having an abundance of experience and knowledge in their subject as two teachers that have taught English for more than 20 years, Mr. Dreisbach and Mr. Krantz are anticipating a lot of change in their field of work. They both acknowledged that these new A.I. programs are going to pose a threat to the way that they — and many other teachers across the country — have been teaching for decades.

“There’s going to be a lot more to it, but I think the solution is to learn a lot, first of all,” Mr. Krantz said, “learn as much as we can about it and then be able to convey that understanding and teach our students how to use it in a way that actually benefits them while maintaining their humanity.”

As La Salle and all other academic institutions begin to navigate policies and gain a better understanding of what A.I. means in an academic setting, they are unsure of exactly what the future looks like.

“It’s a big conundrum,” Mr. Dreisbach said. “It’s a big challenge for us at this particular moment to figure out what we want to do with this. How do we move forward with this? And how do we help people to make use of a tool that’s really useful, but not use it in place of education?”