“We Realized That It Needs To Be Done”: La Salle Implements Opioid Overdose Rescue Kits

Narcan, also commonly known as Naloxone, is an opioid overdose-reversing drug supplied both as an injection and nasal spray form for emergency rescue use.

April 26, 2023

Amid ongoing national and local opioid-related fatalities in recent years, La Salle has equipped its campus with overdose reversal kits as a precautionary measure and an effort to bring awareness to students surrounding the dangers of opioid abuse.

“We realized that it needs to be done and that it needed to be prioritized this year,” Vice Principal for Student Life Mr. Aaron Hollingshead said.

The kits include two doses of Narcan or Naloxone, an opioid overdose-reversing medication, that is administered through the nostrils via a nasal spray device.

The process of obtaining the kits involved adopting a modified version of Clackamas County’s health policy around the kits into the school’s own health and safety policy and a subsequent voluntary education and training sessions for teachers and staff on the current opioid crisis, how the Narcan kits work, and how to administer them, which was led by Ms. Katie Knutsen, a program planner for Clackamas County’s Public Health Department who has played an instrumental role in making the kits accessible to La Salle.

“With fentanyl in particular, we were presented some quite scary data,” English teacher and Narcan training volunteer Mr. Greg Larson said.

As a part of the training session, Ms. Knutsen took time to share information about the opioid crisis in the U.S., explaining to La Salle staff the statistics and dangers of non-prescription opioid use, particularly for young people.

“Things that young people and older people do not consider dangerous are now being laced with fentanyl, and the margin for error with fentanyl is very small because it is extraordinarily potent,” Mr. Larson said. “So people, more frequently than before, think they have something that is safe that is not safe at all.”

According to Ms. Knutsen, any drug from the illicit market and not prescribed from a pharmacy may contain fentanyl, which is 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, and 40% of those drugs contain fatal amounts of fentanyl.

With a majority of teachers, according to Mr. Hollingshead, attending the training session, the kits are now stationed in every trained teacher’s classroom on campus, as well as the main office and athletic facilities. And, looking into next year, Mr. Hollingshead said that one goal is to get a kit accessible to every teacher and also onto every La Salle vehicle to ensure further safety on school trips.

“They’re all over,” Mr. Hollingshead said. “If we were in an emergency, if you just said, ‘Hey, go get one,’ within 30 seconds, you’d have one handy.”

While the reversal drug acts quickly to revive an overdose victim, there are no medical dangers, apart from the rare instance of an allergic reaction, of administering Narcan on a person not actually experiencing an opioid overdose.

This fact is one that Mr. Hollingshead found to be “really empowering,” for staff members learning to administer the kits. “We want people to feel comfortable using them,” he said. “[Ms. Knutsen] showed us the growth in the risk factors but then essentially said, ‘Look, if you’re in doubt, use it, because there’s no harm.’”

Administering or needing emergency use of the kits is also protected by Oregon’s Good Samaritan Law, which means that anyone who is given Narcan, as well as those who administer it to that person, are immune from facing criminal drug-related charges as a result of receiving the emergency medication for a suspected overdose.

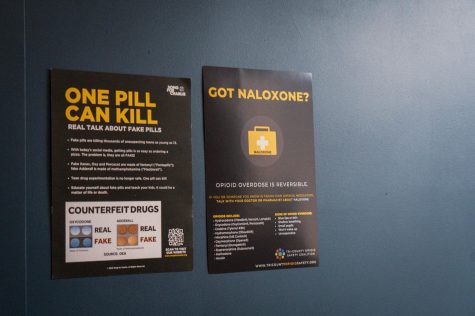

Alongside introducing the kits on campus, posters detailing the dangers of non-prescription drug use can be found around the school building in places visible to students — an effort that Mr. Hollingshead said he made a priority to carry out because “we want more awareness,” he said.

In terms of pre-existing education surrounding opioids, La Salle’s Health teachers added a unit on opioids and their addictiveness into the Health 1 and 2 curricula a few years back, “since fentanyl took the stage [in the U.S.] about a year and a half, two years ago,” Health teacher Mr. Chris Sulages said.

With this, Mr. Sulages, alongside fellow Health teacher Ms. Debbie Schuester, met with Mr. Hollingshead to discuss bringing the Narcan kits to campus this year and are “really big proponents for doing this,” Mr. Hollingshead said.

For Mr. Sulages, having the kits now on campus as a precautionary measure has given him a feeling of security and safety knowing that, in the case of an overdose emergency, they would be accessible like any other first aid supply on campus.

“I think it’s a good thing, for sure, and it’s a simple thing,” Mr. Sulages said.

While La Salle’s introduction to the Narcan kits was relatively recent, Clackamas County’s program made headway in schools about a year and a half ago, according to Ms. Knutsen, following local cases of overdose among young people, particularly students and those in the Multnomah county area. And, even before schools in the county began reaching out about the kits, Clackamas County’s program already had established distribution efforts, which involved partnering alongside organizations like Northwest Family Services in the area.

“A lot of our work has been focused on getting Naloxone out into the community and building education and awareness in the community, so that there are less deaths — so that if there are overdoses, they can be reversed by the medication,” Ms. Knutsen said.

Recently, Clackamas County’s Public Health Department has seen an increase in overdoses across all age groups in the county, Ms. Knutsen explained, with fatal overdoses mostly impacting middle-aged to elderly residents. “The good news is most of the county level data for people under the age of 18 is so small that the numbers are under five,” she said, with 12% of 911 calls reporting overdoses being made for people 10 to 19 years old — though this does not include overdoses within that group that weren’t called in, Ms. Knutsen said.

Despite these seemingly small statistics, Ms. Knutsen explained that having the Narcan kits available to students and young people is “similar to a fire extinguisher,” she said. “You want to have a fire extinguisher on hand before there’s a fire, you don’t want to wait until there’s a fire to get a fire extinguisher.”

Through both their own outreach to schools and also being contacted by school nurses and administrators, Ms. Knutsen said that the program has now been able to get Narcan kits into most schools in the county — now including La Salle.

Although the school’s hope is “never to use them,” Mr. Hollingshead said, their presence on campus is in an effort to both bring awareness to a national issue and provide an extra sense of security amid it.

“The more of these kits we have, the more people who are trained, the more likely it is that we can save a life,” Mr. Larson said. “So if we can save your life and then talk about strategies for support, that seems better than attending a funeral by a lot.”

~

For more information and resources about Narcan and Clackamas County’s program, visit:

How To Use Narcan to Save a Life – The New York Times

Substance Use and Overdose Prevention | Clackamas County

Brooklyn Chillemi • Apr 27, 2023 at 2:35 pm

Thank you for writing about this, Lillian! While it saddens me that these are necessary for our communities, I am thankful that journalism like this is continuing to highlight progress so we can work towards more permanent solutions. <3

Aaron Hollingshead • Apr 26, 2023 at 10:25 pm

Thank you for this important article. Love it!