Fast Fashion Needs To Slow Down

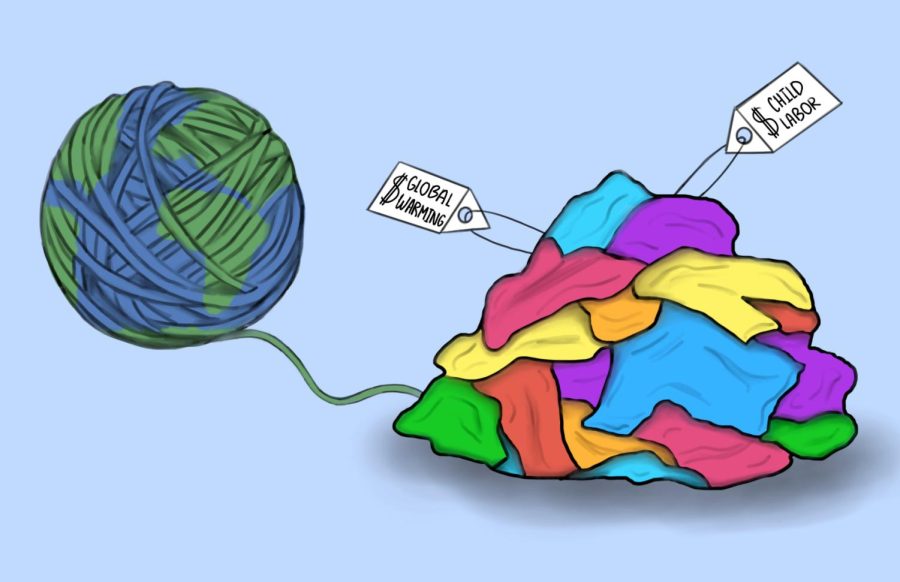

More than 60 percent of synthetic fabrics used in the fast fashion industry are produced using fossil fuels, according to Changing Market’s Fossil Fashion report.

April 20, 2022

Upon walking into almost any mall or clothing store, one can expect to be immediately greeted with racks and racks of clothing. Most of the time, these clothes are cheaply made and cheaply distributed.

Many of these clothes end up in landfills, perpetuating the endless cycle of waste that has immersed the globe.

The impacts of these unsold garments are profound. Despite the fact that the fast fashion industry has been around for less than a century, it has quickly become one of the most economically-powerful industries in the world.

Many people have fallen into the misconception that only brands like Forever 21 and Zara are fast fashion brands, but fast fashion is not about the price tag on the garment, it is about the process in which that garment is made.

Mass production of goods with extremely fast turnaround times on current trends and emerging styles is really what fast fashion is: even designer brands can fall into this category.

Often in fast fashion, piracy and design theft occurs. Small businesses create unique designs and items which then get ripped off by larger companies thus driving site traffic away from small businesses.

The 1960s brought about a new mindset to the clothing industry. Mary Quant, an impactful and popular designer at the time, led a new era of fashion that abandoned a previous era of preserving clothing longevity and led to a wave of disposable fashion.

Around this time, middle and lower-income people had a larger disposable income to spend on entertainment and more extravagant luxuries, like clothing. In order to keep up with these new consumer demands for greater amounts of garments, companies began outsourcing goods production to smaller, less developed countries where they could pay workers significantly less than they would be required to if the work was being done in America.

Now less than 3 percent of clothing sold in the US is made in the United States.

This outsourcing of labor blurs the lines of workers’ rights. Millions of people are working tirelessly in developing countries to produce clothing primarily sold in the U.S., but they do not receive the benefits of working condition codes and rights in the U.S.

Fast fashion consists of a very convoluted supply chain that — because of its complexity — makes it very hard to hold individuals or singular entities accountable for their actions. This makes it easy for bad things to go unrecognized or for them to be swept under the rug.

Baptist World Aid, a nonprofit group in Australia has made it their mission to grade and evaluate clothing manufacturers based on factors like their labor conditions and environmental impacts. “Many apparel companies use convoluted supply chains and production strategies that make extensive use of outsourcing and subcontracting… According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), over 150 million children are victimized by child labor, with North American and European demand for fast fashion driving large numbers of them to the textile and garment manufacturing industries.”

How is this possible? How can a country that claims to defend human rights and justice contribute to such horrific amounts of child labor? How can America not be at least a little more responsible about their role in the supply chain?

In order to prevent further damage caused by climate change and end the exploitation of laborers in developing countries, America must create a more transparent, equitable supply chain and regulate working conditions along with environmental impacts during the creation of fast-fashion garments entering the U.S.

Workers battle excruciatingly long hours in packed factories that rarely meet safety codes. They also receive very little pay for their grueling work. According to a report written by Siddharth Kara, an expert on modern slavery. “Minimum wage for an eight-hour work day ranges from the equivalent of $3.08 (39 cents per hour for unskilled work in the state of Rajasthan) to $8.44 ($1.05 per hour for work in New Delhi). According to the report, most home workers received between 50 percent and 90 percent less than they were owed.”

Almost no workers in developing countries have written agreements with their employers or are a part of a trade union. These unethical conditions don’t seem ideal or even remotely enticing to anyone which is why most of the women that work in these garment factories are led into their position under false pretenses.

Scouts from these factories will go to small, poverty-ridden towns in countries like India and Bangladesh and recruit young women to work for them. They tell the girls and their parents that they will receive three meals a day, fair wages, and a nice home. Almost all of these promises are lies.

Some people may argue that although conditions or wages aren’t ideal, they provide millions of jobs to people who probably otherwise would not be employed. Although this argument has some validity and these factory jobs do supply many jobs, it comes at the price of children’s lives.

These multi-billion dollar corporations are not struggling for money, so why should they not be obligated to pay their workers livable wages? Why should they not be required to know what is happening in the places their inventory is being produced?

The U.S. government and citizens have a moral obligation to ensure fairness around the working conditions and labor practices of goods being produced for American companies and American gain. In general, demanding that outsourced goods are sustainable and don’t contribute to child labor or unfair labor practices is not an unattainable ideal.

For example, New York, the fashion capital of the US, has recently proposed a bill that would require accountability for some of the largest, most influential fashion brands in the world. It would require companies to map at least 50 percent of their supply chain at every step of the way. They would also have to report their usage of water, energy, fossil fuels, and labor wages. If passed, this bill would make history and finally call fast fashion brands out for their role in humanitarian issues and our current climate crisis.

Fast fashion has quickly taken the role as one of the most detrimental contributors to climate change.

From material farming to shipping clothing to the U.S., every step of the way produces so much waste and emissions that it is almost unfathomable.

It is estimated that 92 million tons of waste are dumped into landfills because of fast fashion each year. One point that is often brought up is that many lower-income people cannot afford to buy from sustainable brands, which are usually pretty expensive. This is undeniably true but it also attests to the fact that the fast-fashion supply chain is extremely convoluted.

Why are these perfectly fine clothes not being upcycled, recycled, or given to those who need them?

It’s because corporations benefit from these unsustainable solutions. The Ellen Macarthur Foundation, which focuses on the promotion of a circular economy, said, “More than US $500 billion in value is lost every year due to under-utilized clothes and lack of recycling.”

There is no accountability or organization in this industry, and it is absolutely unacceptable. People die at the hands of this industry and others face the devastating impacts of their contribution to climate change.

It is always important to self-reflect and evaluate your own actions in compliance with fast fashion, but it is more important to work to hold corporations accountable and advocate for workers and the climate’s rights to those in government.

Convenience and lack of research might be the easiest option, but your actions can, and do have meaning.

Think slowly about your decisions before you buy fast fashion.