Acknowledgment Precedes a Solution: The Origins of Sexual Violence

Sexual violence should be seen for what it is: an attempt to assert dominance and fuel the patriarchy.

March 2, 2022

“I’m automatically attracted to beautiful women — I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait. When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything.”

These words were famously spoken by former President Donald Trump in 2005 amid a graphic conversation about groping women. In 2016 — subsequent to his first of at least 20 allegations of sexual misconduct — Trump dismissed the remark as merely “locker room talk.”

This talk is a way to strip women down to merely a sexual commodity; even worse, it was used as a viable excuse for his sexually predatory language.

How could his comment — ridden with vulgarity and dominion — be simplified to purely a byproduct of innate masculinity? What does this say about the crude nature of manhood in America?

It shows the blatant connection between male power, sexual violence, and objectification. It encourages rape culture, and ultimately, fuels male perpetrators’ agendas.

Viewing sexual violence as a product of gender socialization — years of entrenching male domination and female subordination — aids in the creation of equity, for an understanding of the origins of violence must precede a solution to this issue.

Investigating rape as a repercussion of patriarchy, rather than an isolated incident, is the first, crucial step towards a resolution — and ultimately, safety.

An achievement of authentic equity would result in women’s reclamation of bodily autonomy and the initiation of sexual liberation. Women would be empowered to make informed decisions about their bodies without the interference of a patriarchal agenda.

It’s no secret that instances of sexual violence — a vicious attack on someone’s bodily autonomy — are far from scarce, but a key aspect of this epidemic is being overlooked: the intentional attack on women.

Anyone can be a victim of sexual violence; no social demographic is immune to it. All races, genders, sexualities, and ages are capable of rape and of being raped. In fact, every 68 seconds, an American is sexually assaulted. Each victim’s story — no matter what their social identity is — is valid, mournful, and should serve as a call to action.

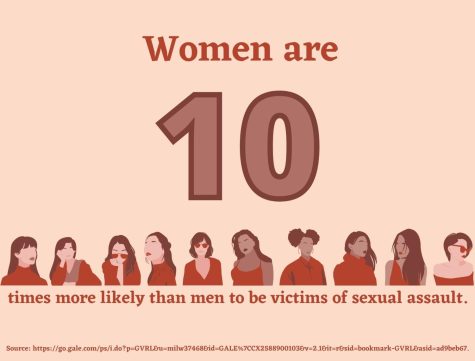

However, there are consistent patterns of identities among perpetrators and victims. The most pervasive dynamic occurs between male perpetrators and female victims. According to Men Against Sexual Assault, women are 10 times more likely than men to be victims of sexual assault. Furthermore, 90 percent of perpetrators of sexual violence against women are men. The recurring phenomenon is indisputable.

Patterns like this have an origin story; it’s not merely a coincidence.

But, for some reason, we aren’t treating it like one. “We have an abundance of rape and violence against women in this country and on this Earth. Though it’s almost never treated as a civil rights or human rights issue, or a crisis, or even a pattern,” as American writer Rebecca Solnit said in her book “Men Explain Things To Me.”

Ignoring the severity of sexual violence ignores the plight of women. Diving into the origins of violence against women will challenge the status quo.

Statistics prove one thing: in most sexual assault cases, women are being exploited at the hands of men. The path to equity will only reveal itself once we understand the origins of sexual violence.

Here is one prominent factor: sexual violence against women is intrinsically linked to the socialization of men as the dominant gender. Within patriarchal society, you are expected to uphold the conventional roles of your gender; conforming to masculinity and femininity solidifies the patriarchy.

Before diving into this, it’s important to note that gender is different from the sex you were assigned at birth; sex is biological whereas gender is learned. Masculinity is a process of assimilation, not an innate attribute of being a man.

Often, within the realm of this so-called masculinity resides pervasive toxicity that strives to achieve power over women. This can be exerted through many means, but often aggression and violence can be the most influential, and consequently, dangerous, methods.

Essentially, practicing conventional masculinity — striving for mental and physical strength, dominance, etc. — automatically gives men the ability to strip women of their autonomy; male privilege in tandem with excessive power often yields a viperous outcome.

Often, a key way that this plays out is through attempting to suppress women’s bodily autonomy and physical dignity through sexual violence. These attacks are more than a violation of physicality. Rather, it’s a dangerous mechanism used to assert dominance and ownership over a woman.

As Solnit says, “Sexual assault, like torture, is an attack on a victim’s right to bodily integrity, to self-determination and self-expression. It’s annihilatory, silencing. It intends to rub out the voice and rights of the victim, who must rise up out of that annihilation to speak.” In other words, it fuels the patriarchy.

At this point, putting two and two together shouldn’t be too hard: sexual violence is not arbitrary. Sex under the patriarchy often fulfills an agenda.

The realization of this bitter reality can yield oxymoronic emotions — fear and relief. It yields fear, for there is more nuance behind sexual violence than what society portrays. Yet it yields relief, because finally, the origins behind rape and sexual assault are being understood, and ultimately, acknowledgment precedes resolution.

In my experience, engaging in conversations about sexual violence — anything from catcalling and sexual harassment to rape — with men typically produces two different but equally harmful responses, usually differentiated by age.

Most adult men I have spoken with — the generation that didn’t grow up in the twenty-first century and wasn’t exposed to consistent media and conversations regarding sexual violence — often reply with a casual, mildly-patronizing “boys will be boys” or a similar statement alluding to inevitability. This harmful declaration insinuates that anything and everything, from disrespect to sexual assault, is a completely justified way to act like a male, and it simply should be dismissed.

This discourse contributes to the insidious nature of rape culture — beliefs that promote sexual violence and involve victim-blaming. It puts the burden on women to prevent sexual violence, rather than focusing on the male perpetrators.

Nevertheless, here is the reality: being a boy does not give you the permission to contribute to rape culture, the patriarchy, and the domination of women. And, any similar argument is futile, for boys and men are fully and utterly capable of controlling their impulses. Rape is not inevitable.

With a collective effort, boys becoming sensitive beings that strive for equity is entirely possible.

The other problematic response emerges after adolescent boys agree with the prior statement. This, in and of itself, is a monumental occurrence; the current generation of teen boys acknowledges the prevalence of sexual violence and advocates for prevention. They seem to understand that all men have an obligation to work towards change.

However, subsequent to these reassuring statements, in my experience, often emerges a series of predictable statements: “I would never rape someone,” followed by, “asking for consent seems unwarranted though,” and finally, “I’m an exception to ‘all men,’ right?”

Here is the thing: simply not having sexually assaulted someone doesn’t remove you from the problem. For example, objectifying women’s bodies, trivializing rape, catcalling, and slut-shaming all contribute to the insidious nature of rape culture.

The genuine advocacy seems to falter as they are expected to engage in the tangible practices of preventing rape — asking for consent, believing survivors, being open and communicative with their partners, etc. — yet they still feel like an exception to “all men.”

Often, these actions, or lack thereof, aren’t because they are ill-intentioned or malicious, but they don’t understand rape and sexual assault aren’t isolated incidents; they are borne out of male dominance — a concept that is not unfamiliar to them. Men have an inherent ability to violate a woman’s body, and teenage boys are not exempt from that ability.

It’s not a matter of whether a man thinks he would sexually coerce someone or not; it’s about whether they understand the connection between patriarchy and sexual violence or if they will let their subconscious impulses — to assert dominance and masculinity — affect their rational thought. Understanding the ways you perpetuate inequality is intrinsic to changing the status quo.

Now, although sexual violence persists, we are beginning to embark on the journey to equity; the journey may feel leisurely, but proof resides in the successes that are often camouflaged by the setbacks.

A contemporary milestone in the fight against sexual violence stands out among all others: The Me Too Movement. Primarily completed through social media, victims would share their stories in hopes of showing the abundance of sexual harassment in our current environment.

Simultaneously, the movement sparked global change — intellectually, legally, and socially. It empowered women to share their stories, even when the potential backlash was daunting. One example of this occurred in 2018 when professor Christine Blasey Ford accused Supreme Court Nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her more than three decades ago.

“I’ve had to relive this trauma in front of the world,” Blasey said.

In response, Kavanaugh was confirmed as a Supreme Court Justice. While justice didn’t arrive for Ford, her courage pointed us toward equity; she defended our democracy, demonstrating the ability to call out men in power.

Furthermore, a 2019 poll showed that 76% of Democratic voters and 49% of voters overall agreed with the statement that “one reason Justice Kavanaugh was confirmed is because white men want to hold onto their power in government.”

In other words, nearly half of the voting population recognized an ulterior motive — one that didn’t involve fighting for Ford’s justice — underlying the case: boosting men’s social domination.

Recognition is a success. Although equity remains distant, acknowledging the reality is a substantial step towards change.

Without a doubt, we allow our examination of inequity to prevail over our envisionment of equity.

What does sexual liberation even look like? How would terminating sexual violence alter our lives? It would be momentous for the whole gender spectrum — even men.

Liberty would consume us. Gender roles would cease to exist, giving us free reign of our gender expression.

Eradicating sexual fear would restore the strong female image, which would pertain to all things. It would begin a societal reform, in which securing bodily autonomy was a deeply held value by and for all.

All gender identities could coexist with the mutual understanding that safety is assured.

These aren’t luxuries, but they also aren’t our reality. The reality is grim. The reality means becoming accustomed to the fact that the prior 68 seconds unveiled a new victim into a world of sexual trauma.

But, our current reality doesn’t have to be permanent; change is fully and utterly possible.

Anna Waldron • Mar 3, 2022 at 9:55 am

This is such an informative and well written article. Thank you for taking on such an important topic, as always. I appreciate the coverage on this, as it is so devastating, yet so normalized. Great job Maya!