The Violence in Myanmar Reflects the Decline of Democracy Everywhere

The streets of Myanmar, once peaceful, have now erupted in violence.

March 31, 2021

In Myanmar, a Southeast Asian country bordering China, India, and Thailand, violence has dominated the streets after a military coup on Feb. 1, as soldiers continue to clash with peaceful protesters in an ironfisted attempt to crush the country’s hopes for democratic freedom.

Many of the scenes from Myanmar are horrific. For all of us here in the U.S., it could be easy to turn a blind eye to what’s happening there, especially after the tumultuous year that COVID-19 has brought. After all, Myanmar is on the other side of the world, and we all have our own little worlds of problems facing us each day.

But we should all care about the downfall of democracy in Myanmar. The cruelty enacted by the Burmese military in the past weeks has been a brutal show of greed and inhumanity, leaving hundreds of innocent people dead.

Moreover, there is immense relevance in the parallels that can be drawn between the attack on civil liberty in Myanmar and the endangered state of democracy in America — and for that matter, across the world.

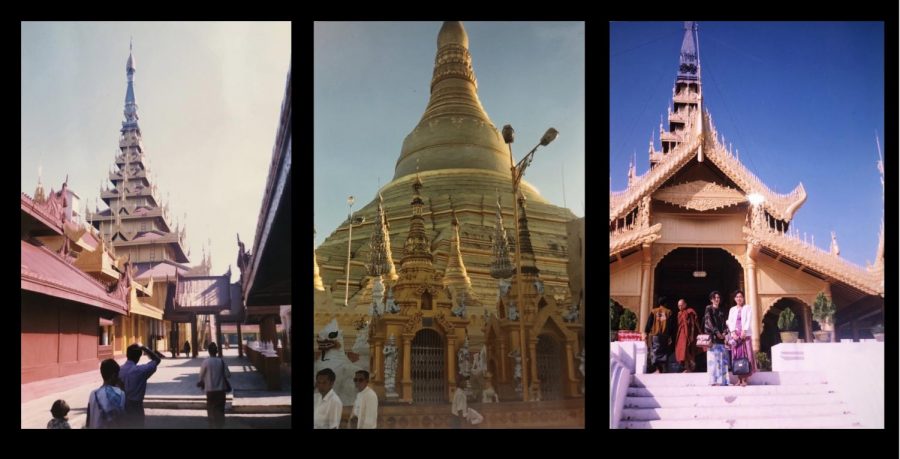

When my dad was eight years old, he and his family packed up and moved from their home in Yangon, Myanmar to a new home in the United States — a nation that was, to my dad, foreign and almost mystical, an exciting land filled with fancy amenities like cars, phones, TVs, and the ability to have enough food.

When I say they packed, I mean lightly. My dad said he remembers his family taking a few suitcases of belongings for all seven of them, recalling that his father later mentioned he had packed materials worth, in total, just 200 U.S. dollars.

Since my dad was only eight years old, he didn’t have much to leave behind in Myanmar. For his parents and older siblings, however, there was much greater sacrifice. My aunt and uncles, who at that point had reached or nearly finished their teenage years, completely pivoted their lives, abandoning everything they had known to chase the prospect of something better.

My grandparents left behind a community of friends and family, and the comfort and stability that stemmed from it. My grandfather, who for years had climbed the ranks of the Burmese government to become the country’s head of forensics, departed from his status to move his family to the U.S., where he was considered uneducated and without a degree. He went from being a lead chemist in his nation’s government to an assistant in a Red Cross lab, my dad recalled, where he cleaned tools and supplies.

Despite the many sacrifices it took, my dad’s family was excited to move to America. My grandfather had been working for years, longer than my dad can remember, to gain government approval (both Burmese and American) for immigration to the U.S. My dad and his family counted — and still count — themselves fortunate to be able to escape the poverty and oppression that reigns in their home country.

There was little to no individual freedom in Myanmar, my dad said, and the government, which was one and the same with the military, was corrupt and oppressive.

“Everybody knew it was a bad place,” my dad said. “It’s not a desirable place to raise a family — the whole country, I’m not talking about [just] cities.”

In Myanmar, which was formerly called Burma, there were no civil assurances like the natural license to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that is revered in America.

“The country was run down by a few leaders who had nothing in mind to make the country prosper, but all for themselves,” my dad said. “We knew that where we lived, in that country, there was a very limited chance and opportunities to prosper, as in getting a good education, being able to get a job, and provide [a] living for yourself and your family. In Burma, we knew it was very little chance for that type of opportunity, so your life was going to be very hard.”

Life in America was different, and in some ways uncomfortable, but overall better. My dad learned English and adjusted to being called by his English name. My grandfather earned his teaching certification and taught high school science. My dad and his siblings were all granted greater opportunities and education than they would have been able to pursue in Myanmar, as well as the ability to provide their own children with even more opportunities.

“Our government allows for so much more individual freedom and rights of people,” my dad said. “Our government here has more checks and balances, where one entity doesn’t become all-powerful… Although I know there are corruptions, it’s not the same level of corruption that occurs in many places, especially in places like Burma, where there is very little accountability for officials who are placed to help the people.”

Growing up in the U.S., participating in democratic freedoms, and enjoying the civil liberties that they moved to America to attain, my dad and his siblings were also happy to see that back in Myanmar, the Burmese people and government started making strides towards democracy.

My dad and his siblings watched as in 2015, Myanmar’s National League for Democracy, headed by civilian leader and Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, won the parliamentary election. It was the first time since 1962 that the Burmese military — called the Tatmadaw — was not in control of the government, though the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi and her democratic party was shared with the military during the years following her election.

“We were very happy, just so full of optimism for the future of the country and the people,” my dad said. “If their government is a democratic government that supports the people, even if they are not always doing well, say, by Western standards, I think those people would be happy in their homeland. So we were all so excited to see that change happen.”

Throughout her rise as a pro-democratic figure, Aung San Suu Kyi — despite international criticism for defending the Tatmadaw’s assault on Rohingya Muslims — has been a heroine for the Burmese people, an icon representing the ascension of democracy where it’s previously been absent, and a beacon of hope for a country long ravaged by the forces of colonization and military rule.

“The Burmese people were sort of under oppression the whole time,” my dad said. “She’s the first one to bring democracy and hope for freedom for the general Burmese people… She’s for the people.”

But now, my dad, his siblings, and many others are saddened by the recent events in Myanmar, where the Tatmadaw has seized full power with a military coup, detaining Aung San Suu Kyi and other pro-democratic figures on obscure charges.

In Myanmar’s 2020 election, Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy again won the majority of the parliamentary seats in a landslide vote. The Tatmadaw rejected the election, claiming without evidence that the results were fraudulent (sound familiar?), then carried out a coup d’état on Feb. 1 — the day that Myanmar’s new parliament was set to convene for the first time to certify the 2020 election results.

Since the coup, unrest has erupted in Myanmar, with millions of demonstrators taking to the streets in peaceful protest against the military’s ruthless tactics to squash democratic freedoms. Protesters have been met with violence from the military, resulting in more than 420 deaths since the Feb. 1 coup.

The entire country has been swamped in death and violence essentially nonstop since the military takeover. Last Saturday, March 27, appeared to be the bloodiest day since the coup — the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners documented that at least 90 people were killed in that single day, and Myanmar Now reported a death toll of at least 114 people. Among those killed on Saturday were a 5-year-old boy, two 13-year-old boys and a 14-year-old girl.

I wondered how my dad felt, seeing such violence occur in his home country and hearing the news about the military crackdown, which struck down the hope that had previously been ascending in the nation.

I wondered how it felt knowing that if things had gone differently for him, if my grandfather hadn’t been able to obtain immigration permission or hadn’t had the means to do so, it could have been my dad and his colleagues demonstrating on the streets of Myanmar, risking their lives for the basic freedoms that we all enjoy every day in the United States.

I wondered how it felt, from his perspective, reading about the young women who have been at the forefront of the anti-coup movement in the face of uninhibited violence — how it felt that it could have been his teenage daughter who hugged her father goodbye before being shot in the head and killed by security forces at a protest, which is what happened to a girl named Kyal Sin on March 3.

Along with sadness, my dad said he feels both angry and helpless.

“These are peaceful people who are not armed, just regular young people [and] families who are protesting [for] the basic human right to live in a society that’s free, a government that’s represented by them and for them,” my dad said. “It’s just not right for unarmed civilians and families and kids to be under this sort of brutal military who’s using weapons and guns to force the agenda of a few who want to stay in power.”

Sitting at home, on the other side of the world from Myanmar, I also feel helpless. Myanmar’s hope for democracy, a cascade of light that had been descending on a country long shrouded by darkness, was crushed ruthlessly and abruptly by the iron fist of an oppressive regime that many thought Aung San Suu Kyi and her garnered support for democracy could overcome. In Myanmar, violence and dictatorship prevailed. The side with the guns won.

In the U.S., the realities of countries like Myanmar seem incomprehensible. The poverty and oppression in places like Myanmar are more than distant from the dream of prosperity and opportunity we’ve supposedly achieved here in the States. ‘Third World’ to our ears means ‘Other World,’ and what has happened in Myanmar is seemingly unimaginable here in America, where our foundations of democracy are supposedly unshakable.

But if we’ve learned anything from the recent months and years of political tension in America — including an outpouring of lies from a power-hungry administration looking to do anything it can to maintain its grip on authority — we’ve learned that democracy is fragile.

Despite how different my dad’s life in America is from the life he might have led in Myanmar, and despite how otherworldly the Burmese people’s struggle against the Tatmadaw might seem to us, our democracy is not unbreakable.

In Myanmar, it seemed like they were making meaningful progress towards civil liberties, but that progress was eliminated with one swift swipe of a tyrannical hand. The Burmese military didn’t like the results of the country’s democratic vote, and so fabricated false claims of fraud. When those claims didn’t work and Myanmar’s election committee upheld the results, the Tatmadaw turned to its final resort: Force. Violence. Disruption.

The events following Myanmar’s 2020 election are eerily similar to those following our election in the U.S. When the Supreme Court rejected the previous administration’s attempts to discount the election results, proponents of a false narrative of election fraud turned to similar tactics — force, violence, and disruption at the hub of our democracy to try to stop a “steal” of something that was never stolen in the first place.

Fortunately, democracy prevailed in the U.S., and the people’s vote was certified — unlike in Myanmar, where their system lacks the checks, balances, and distribution of power that our Constitution entails.

Still, my dad said, “it’s scary that we came that close to what’s happened in real life in Burma,” and I agree.

Though the U.S. was able to preserve its democracy after the chaos of Jan. 6, the storming of the Capitol — as well as the deterioration of civil liberty in Myanmar — serves as an exemplar of the decline of democracy everywhere. Democracy is under siege worldwide, and the U.S. is no exception.

Although the country as a whole has ostensibly moved past the Capitol riot, eventually transitioning into the new administration, there are still millions of Americans who believe the election was fraudulent, despite a lack of evidence.

As we’ve seen in Myanmar, the unfortunate truth in many places is that civil liberty and the right to a free and fair government are not always ensured or automatic. Though the right to democracy is intrinsic, the preservation and retainment of this right is not. Even in America, where my dad and his family have enjoyed so much more freedom and opportunity than they would have in Myanmar, democracy is fragile, and we must work to protect it.