As the Pandemic Exacerbates Learning Inequities, Further Action is Needed

If we allow these disadvantages to continue hindering the learning of low-income, already underserved students, we will create irreversible harm for an entire generation.

November 11, 2020

Battling weak internet connections, typing essays on minuscule smartphone keyboards, and attempting to navigate alien learning platforms without sufficient support from parents or teachers — these are just a few of the challenges that low income, already-disadvantaged students will grapple with this school year, as their higher-income counterparts are able to propel forward in their learning.

Staggering inequities and an expanding opportunity gap are not new to the United States education system. However, as millions of K-12 students in the U.S. continue the school year in a remote setting, disparities in education will only worsen. The exacerbation of learning inequities is an issue that deserves more recognition and urgent action in order to prevent an entire generation of students from permanent harm.

What disadvantages has the pandemic created for low-income students?

It’s first important to be aware of how this problem has arisen so that we can understand the direness of the situation and the ways we need to address it.

While many factors can create disadvantages for students during digital learning, lack of access to a stable internet connection and a suitable device are two of the greatest challenges faced by many low-income students trying to learn remotely.

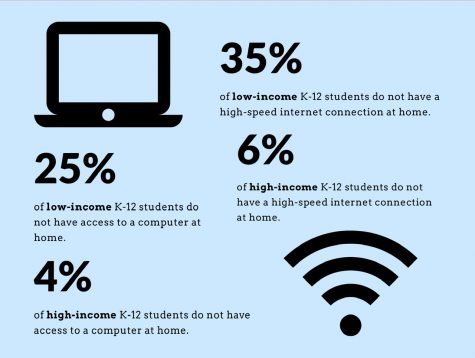

According to Pew Research Center, roughly one-third of households with K-12 students and an annual income below $30,000 do not have a high-speed internet connection at home, and one in four of these households lack access to a computer at home. Comparatively, of households with K-12 students and an annual income above $75,000, just 6 percent do not have a high-speed internet connection, and only 4 percent are without a computer.

Based on these startling statistics, low-income students are far less likely to be able to complete assignments or attend meetings with digital learning in place.

It’s also important to consider the support that students, especially those in younger grades, receive from parents at home.

Just around 24 percent of parents with an income below 250 percent of the federal poverty line are able to work from home, compared to 54 percent of parents with an income at or above 250 percent of the federal poverty line. Since higher-income students are more likely to have a parent who is working from home during the pandemic, they are more likely to receive assistance during the day if they encounter difficulties while learning, whereas low-income students are less likely to have this same support.

Moreover, the type of instruction students receive can create disadvantages for already deprived students. In a study from the Center on Reinventing Public Education, researchers looked at the pandemic learning policies of 477 school districts. The study revealed that only a fifth of these school districts required live teaching over video, and that wealthy school districts were twice as likely to provide such teaching as low-income districts. This indicates yet another disadvantage faced by low-income students amid the pandemic: they are less likely to reap the benefits of live teaching during digital learning.

In addition to examining some of the resources students have access to while learning, it is crucial to consider how the basic needs of students are being met during this time. Low-income students are much more likely to face food insecurity during the pandemic, with four out of 10 low-income Americans struggling to afford enough food. If students are not getting enough to eat, how can they possibly focus on schoolwork?

Food insecurity and other basic unmet needs can create grueling difficulties for low-income students, making it almost impossible to learn. This challenge adds to the list of disadvantages low-income students are forced to overcome to receive the same education handed to higher-income students.

How will these exacerbated disadvantages worsen learning inequities?

By putting emphasis on an entirely new set of factors that affect students’ education, digital learning will further divide more fortunate students and their disadvantaged peers.

Already, research has shown that just 60 percent of low-income students are regularly logging into online instruction, whereas the turnout among high-income students is 90 percent. This research displays how the disadvantages low-income students face have led to decreased engagement.

One study from researchers at Brown and Harvard examined how Zearn, an online math program, was used both before and after schools closed in March. The analysis found that, through late April, student progress in math decreased by about half in classrooms located in low-income ZIP codes, by a third in classrooms in middle-income ZIP codes, but not at all in classrooms in high-income ZIP codes.

Ultimately, it is predicted that the disadvantages digital learning has compounded for low-income students will lead to a greater loss of learning for some students and widening of the achievement gap — unequal academic performance among students.

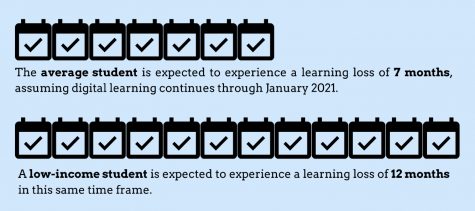

As an example, experts estimated that, assuming digital learning continues through January 2021, the average student will experience a learning loss of seven months, while a low-income student is predicted to lose over 12 months of learning in this same time frame.

Why do we need to take action, and what can be done to reduce inequities in education?

If we allow these disadvantages to continue hindering the learning of low-income, already underserved students, we will create irreversible harm for an entire generation of students.

According to Wayne Lewis, the former Kentucky Education Commissioner and Dean and Professor of Education at Belmont University, kids that lose an academic year tend to be disadvantaged for the better part of their academic careers, and for kids that lose two academic years, the chances that they’ll catch up are slim to none.

Extreme learning loss for already disadvantaged students will not only lead to detrimental economical impacts, but also a more divided, unequal society. Most importantly, it’s unfair to these students, who are disproportionately impacted by the already-damaging effects of the virus.

In order to avoid these impacts, it is imperative that more people understand how disparities in education are growing so they are able to take action against these inequities.

In combination with further education and awareness, action is necessary on a federal level and a local level, with both government and community leaders making targeted efforts to provide low-income students with the same resources and opportunities as wealthier students.

In terms of how the La Salle community should consider this issue, all students, especially those coming from wealthier backgrounds, should recognize the privileges we receive through a private education, and work to uplift disadvantaged students both inside and outside of our school community.

La Salle students and staff can spur change by working with neighboring schools — like La Salle has done previously through partnerships with Lot Whitcomb Elementary — to make sure students across schools with varying income-levels have access to necessary resources and support while learning remotely. This could mean creating additional service opportunities like food or clothing drives to support disadvantaged students, or even making more education-specific efforts, like tutoring programs or larger school supply drives. There are a number of things we can do as a school to make sure all students have access to equal opportunities in their education.

While targeted changes will address education inequities more directly, it is also necessary to collectively work towards a more equal society if we ever want to completely close the opportunity gap. As Jack Schneider, an author and scholar of education history and policy at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell has pointed out, the achievement gap is a result of our unequal society. In order to get to the root of inequities in our education system, we must address the systemic inequities present in our society.

As the pandemic continues to exacerbate disparities in education, it is more important than ever that we recognize the severity of this issue and work towards leveling the playing field for students as much as possible.

As Nelson Mandela once said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

Now, it’s up to us to make sure that all students have access to it.

Alanna O'Brien • Nov 12, 2020 at 9:18 am

Mary, thank you for your work on this article that addresses such an important topic. Your call on our La Salle community to get involved and support our neighborhood and local communities is spot on. I love when I am inspired by La Salle students, and I hope we can take your words to heart.

Rachael Kwiecinski • Nov 12, 2020 at 9:15 am

Thank you for the insightful article Mary. The statistics are staggering.