The following review contains spoilers for the film.

It wouldn’t be a stretch to call “Lilo & Stitch” (2002) one of the wackiest, most contemporarily beloved treasures of Disney’s vast animated vault.

The film follows Experiment 626, a fluffy, blue, galactic fugitive who crash-lands his stolen space police cruiser on the Hawaiian island of Kauai and somehow passes for a rather ugly dog. To avoid capture by Dr. Jumba Jookiba, the mad scientist who created him, 626 gets himself adopted by lonely six-year-old Lilo Pelekai, who names him Stitch and eagerly shoulders the responsibility of teaching the genetically-engineered weapon of mass destruction how to love.

How do you replicate something like that?

For director Dean Fleischer Camp and the rest of the team behind the 2025 revival of “Lilo & Stitch,” the answer is simple — you don’t.

Rather than ride the coattails of its animated ancestor, “Lilo & Stitch” breathes new life into the beloved classic, artfully taking creative liberties while remaining loyal to the original’s message of love and family. Though still hilarious and tear-jerking, it explores the lives and experiences of Lilo (Maia Kealoha) and her older sister Nani (Sydney Agudong) with more depth than before.

At eight years old, Kealoha isn’t much older than Lilo, portraying some serious ups and downs throughout the movie’s hour and 48 minute run time.

Considering Kealoha’s youth and the fact that this is her first major motion picture, her performance is impressive — especially in such a meaningful, difficult role.

Still coping with the recent loss of her parents, Lilo experiences bullying, alienation, guilt, and near-separation from her sister. That change of custody is interrupted, however, when Lilo protects Stitch from capture by Jumba (Zach Galifianakis) and, in the process, nearly drowns for the second time in the movie.

Needless to say, she goes through a lot.

Kealoha brilliantly handles Lilo’s emotional rollercoaster, wonderfully executing everything from melancholic guilt to uncontrollable, six-year-old glee. No matter how well-written a script is, without talented actors behind it, it’s just that. Lilo is already lively and lovable, but Kealoha’s vibrant, bursting energy — both on and off screen — really brings the character to life.

She does exactly what a live-action adaptation is meant to do — make the character human.

Agudong’s performance as Nani equally exemplifies this, taking on a soul and narrative that was partially missing in the original. Nani is a child herself, grappling with the grief of losing her parents at the same time that she is struggling to take care of a boisterous, often troublesome little girl that she is in danger of losing.

She turns Nani into a person independent of her relation to Lilo, as we get to see more of her life before the pair was orphaned — her passions, her dreams, and the future she gave up on to provide for Lilo.

These directorial choices surrounding Nani are largely why I enjoyed the movie so much. Being the big sister of a little wild child myself, I felt like I could relate to Nani better when she was more of a fully-developed character.

Giving Nani a story and a life outside of Lilo makes her feel far more real, and her relationship with Lilo is remarkably organic and touching.

A live-action remake needs humanity. Agudong and Kealoha give us humanity.

The remake is more introspective and realistic, which I appreciate, but it has been critiqued as losing some of the wild imagination of the original. And as much as I loved this film, I have to agree; in becoming more human, it seems slightly watered down, particularly where Stitch is involved.

Stitch — voiced by Chris Sanders, the director of the original — feels more like the rambunctious pet he’s pretending to be than the intelligent, deeply-written crowd favorite he is. His part in the movie, while indispensable and full of that madcap hilarity that made the 2002 version so charming, is reduced.

The 2025 “Lilo & Stitch” is just more Lilo than Stitch.

Stitch is still delightful to watch — impish, unpredictable, and lively. But there’s a notable lack of some of the scenes that endeared him to original audiences, such as Lilo’s attempts to mold Stitch into the “model citizen,” i.e., Elvis Presley.

Most excruciating is the removal of an essential scene to his character, in which Lilo reads him the story of the ugly duckling. Never having had a family, Stitch identifies with the lost baby bird, and it marks a turning point for him, sparking his desire for a family of his own in Lilo and Nani.

Without this scene, Stitch’s shift to goodness, while still heartwarming, unfortunately doesn’t make much sense.

The remake adjusts a lot, shifting positions and bringing in new ones, but the basic story remains intact. While some fans oppose many of these changes, I think they suit a live-action adaptation well, bringing it down to Earth.

More importantly, these modifications succeed because the heart of the movie remains the same: “Ohana means family, and family means no one gets left behind or forgotten.” It’s central to the story, a mantra repeated by Nani, Lilo, and even Stitch in the end.

Tūtū (Amy Hill) — an original character, like Mrs. Kekoa (Tia Carrere) — is the seventy-something next door neighbor and pseudo-grandmother of Lilo and Nani who demonstrates the concept of ohana best.

Nani is adamant about staying with Lilo, but Tūtū encourages Nani to pursue her discarded dreams. In the end, she eagerly opens her home to Lilo to make that possible, and Nani accepts her full ride to study marine biology at university. Pleakely, who joins the family in the end alongside CIA agent Cobra Bubbles (Courtney B. Vance), kept his portal gun, circumventing the separation.

In a classic fairytale ending, the two sisters will always be connected no matter the distance.

Through Tūtū, Nani and Lilo find that their ohana is a lot larger than they thought, and that when they need it, their community will support them wholeheartedly. But Camp’s decision to change the movie’s ending like this was very risky, and it has come under some serious fire by dedicated fans and analysts of the original.

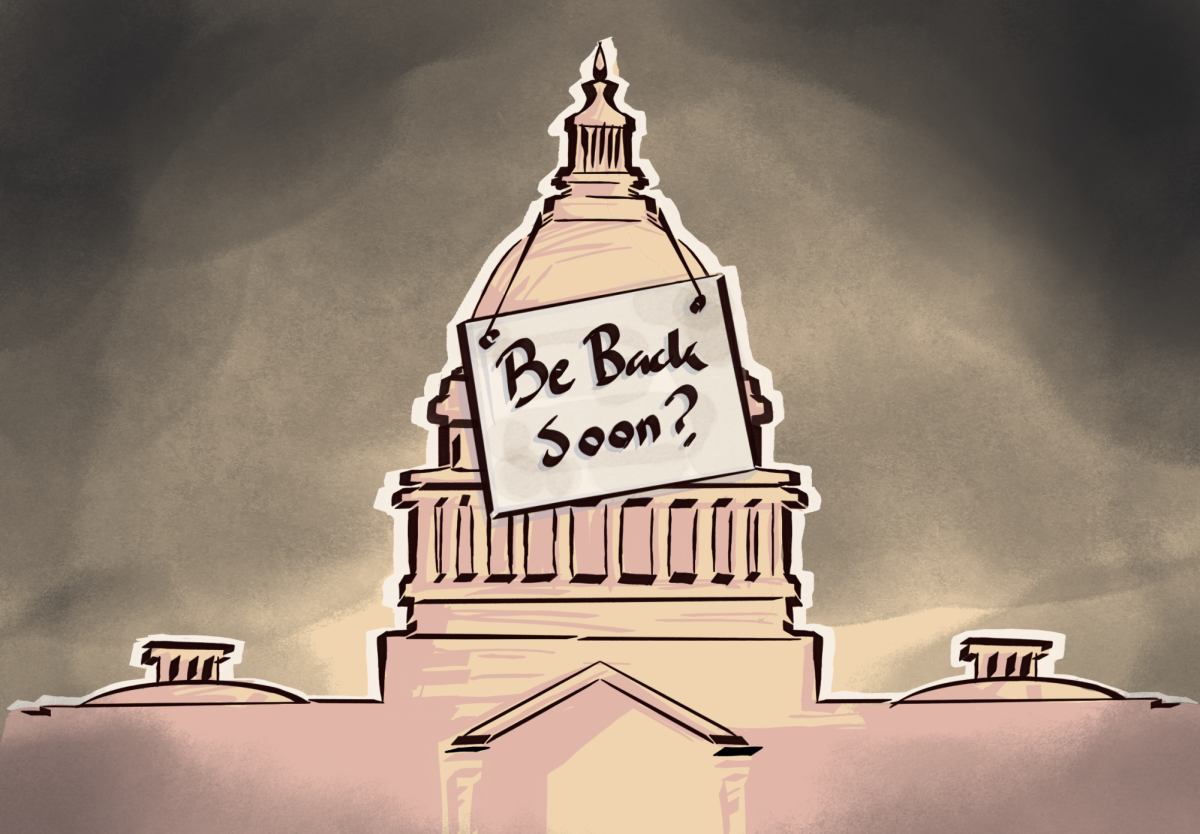

The pushback largely stems from a widely-accepted interpretation of the original film’s events as an allegory for the U.S. government’s annexation of Hawaii and their oppression of Hawaiian culture, with Bubbles as the government and the Pelekais as Hawaii.

The night before Bubbles comes to take custody of Lilo, Nani even sings “Aloha ‘Oe.” The song was written by Queen Lili’uokalani, the last Hawaiian monarch, and it’s often understood as a farewell to the traditional Hawaiian way of life and a symbol of resistance for the people.

Many feel like the altered ending is another instance of Hawaiian cultural erasure.

This is very understandable. But the remake doesn’t remove the elements of conflict between the sisters and the government; it just has a more realistic approach, honing in on the Pelekai household’s emotional volatility and overall instability with Nani unemployed. It examines complications that weren’t discussed originally, such as the cost of living in Hawaii, the highest of any state.

With such a paradigm shift, the remake should be viewed as its own movie rather than in comparison to the original.

Instead of the relationship between the sisters and the government, it zeroes in on themes of loss, sisterhood, recognizing when you need help, and learning to lean on your community. Nani is not a mom; she’s an older sister dealing with grief, disappointment, and stress as her own person. She’s not equipped to take care of Lilo, but she also doesn’t want to abandon her to the foster care system.

It’s important to note that Nani’s character was given an update, not an overhaul. She’s still fiercely protective of her little sister — it took pushing from Tūtū and Lilo both to convince her to take care of herself. They want what is best for Nani, too, because they love her just as much as she does them.

Regardless of the version, the movie’s message is consistent and important. Ohana means family, and family can come from anywhere and anyone, no matter how unconventional or unexpected. No one gets left behind or forgotten — not Lilo, Stitch, Bubbles, Pleakley, Tūtū, David, or Nani. “Lilo & Stitch” shows us that ohana isn’t restricted by blood — it’s the people you change, love, and care for.

This movie is a step in the right direction for Disney, hopefully indicative of an eventual recovery to their pre-pandemic quality. It’s the perfect balance between originality and loyalty, and it takes on new life through the skilled actors, writers, and directors who developed it.

I urge nostalgic moviegoers to see “Lilo & Stitch” as its own film, packed with talent, creativity, and the spirit of innovation and magic that is so quintessentially Disney.

It may not be able to stand up to the cherished original, but as far as Disney’s live-action reboots go, “Lilo & Stitch” is fantastic — hilarious, heartfelt, and definitely worth the watch.