Does it matter if I’m sinking when everyone thinks I’m swimming?

That is the question I’ve repeated nonstop in my mind since coming to La Salle, where the pressure and expectations of success get to me even when I know that realistically, it’s not a healthy thing to think. It settled me into a repetition of unhealthy thoughts of doing better and needing to be better at the cost of my own health.

My negative self-talk became my reality.

Transitioning from a public middle school to La Salle was a big shift — where before A’s came easily to me, now A’s are a stretch, even when hours of my life outside of school are dedicated to trying to achieve them.

I had pushed myself all through middle school with the sole expectation that B’s were failing and A’s were what really mattered. You’d think that would mean I was ready for a college preparatory school, but that wasn’t the case.

Through most of this year, I’ve continued to push myself, and I expect that I will continue to even after this piece and in the coming years. While motivation isn’t necessarily bad, what gets me is when people tell me how great I’m doing — how I seem to understand stuff so easily.

At some point this year, the natural human reaction of burnout began to catch up to me, and I felt drained almost constantly. It came to the point where even teachers noticed, saying how since second semester started, I wasn’t the same.

I was distancing myself.

When I heard that people were noticing this, there came this fleeting moment where I was relieved because I felt seen for the first time in a long while. But that’s when fear and reality settled in, and I redoubled my efforts, because my pain being seen was a vulnerable feeling, which my brain associated with danger. I smiled brighter, laughed when needed, and never said no to those who needed my help.

I began to realize just how easy it was to fake a smile that is believable enough despite the fatigue that was settling in my lungs like sediment, and it seemed to only make things worse.

Now, there is something that I get a lot from people, whether teachers, friends, parents, or grandparents — comments about how well I’m doing and how glad they are.

For me, that just goes to show how good I’ve gotten at masking my struggle, when in reality, most days of the week, I feel barely afloat, and I struggle to keep up with schoolwork, let alone help others with theirs.

This is duck syndrome.

A phenomenon in which students present a calm façade of relaxation, happiness, and achievement within their environment, duck syndrome often presents in academic settings, such as colleges and high schools, where pressures to succeed and compete weigh on students.

Just like how even though ducks calmly glide across water, they have to rapidly and relentlessly paddle their feet to stay afloat, some students may present an appearance of ease and effortlessness while gliding through their commitments both academic and within their personal lives.

This façade people put on often does an excellent job at hiding the reality of their situation and the challenges they’re currently shouldering to meet high expectations.

I’ve learned to be excellent at projecting such a façade.

I have a habit of just pushing and pushing myself, and even when I hit the ground with exhaustion, I’ll just push myself harder, telling myself phrases like “no pain no gain,” or “it’s preparation for college.” My favorite was “pain is only temporary.”

Yet, when the second semester started this year, it felt like everything was catching up to me, and I just wondered: Why am I trying?

If you asked me that, or what I hoped to accomplish through all my efforts, I genuinely could not tell you. Not because I don’t want to, but because I don’t actually know myself.

Except you wouldn’t ask.

This is because you’d see a smile, decent grades, and a caring personality who helps others with their problems and work first. You probably wouldn’t wonder about the price of perfection.

You wouldn’t see beneath the surface just how exhausted I actually am.

People often don’t tell others that they’re struggling because it’s hard to see others become uncomfortable and not know what to do. So the person ends up comforting them, and redoubles their efforts in “looking okay.”

For those who are like me, I want you to know that I get it. It’s difficult, and exhausting, but you’re not alone even when you feel that way. And I’m also here to implore others to look a little deeper past the successes and smiles and “I’m okay”s.

Because in our generation, the simple phrase of “I’m okay,” has become:

- I’m not … but I’m supposed to be.

- I’m not … but I don’t know what to say.

- I’m not … but aren’t I better off than I could be?

- I’m not … but I have to be.

A friend once told me this quote: “People still drown when in five feet of water, compared to those who drown in oceans.”

You can’t compare your stress and struggles to others. It’s not an easily measurable metric unit; it’s a feeling that everyone feels and deals with differently.

Most days of the week come as a struggle to me, and focus is often hard to find in classes. Teachers often tell me “you just need more practice,” while other adults scold me for “letting my grades slip.”

That seems to make things worse. It’s not because I’m not open to their constructive criticism, but because I already tell myself that day in and day out, and so the phrases have been rubbed dull in my ears.

The question I think many of us need to begin asking ourselves is: How much effort do we really need to put into this perfect façade, and to our work?

It’s not to be said that no effort should be made towards schoolwork, but we should start learning now, while in high school, how to balance ourselves with that work while in a more competitive environment.

I get that most people just want to go to sleep without the academic pressure weighing on them, and while we can’t fully take that away, we can handle it one step at a time. Even if during those steps sometimes you need your friends to lift you up and get you going.

We can’t do everything ourselves.

It isn’t easy to do — to allow ourselves to rest and ask for help.

Even with writing this article, I know I’ll still go through some days with that perpetual stress. But by publishing this piece, I’m also putting down the hope that anyone who feels like me will know they’re not alone.

Though the term is normally used in college and university settings, duck syndrome is a phenomenon that high school students often face.

If we want to raise awareness about this issue, and support students who are experiencing it every day, it is crucial to have discussions, especially in a competitive environment like La Salle.

Chris Babinec • May 8, 2025 at 9:29 am

Oh wow. What a gorgeous piece of writing. What a wonderfully poetic piece of prose. The experiences of the writer are deeply felt while reading this. The writer both explores their individual experience while simultaneously touching on the broader human experience.

When the writer shares, “When I heard that people were noticing this, there came this fleeting moment where I was relieved because I felt seen for the first time in a long while. But that’s when fear and reality settled in, and I redoubled my efforts, because my pain being seen was a vulnerable feeling, which my brain associated with danger. I smiled brighter, laughed when needed, and never said no to those who needed my help.”

This is what we do, isn’t it? Why? What drives us to “succeed”, to strive for “perfection”, to resist vulnerability?

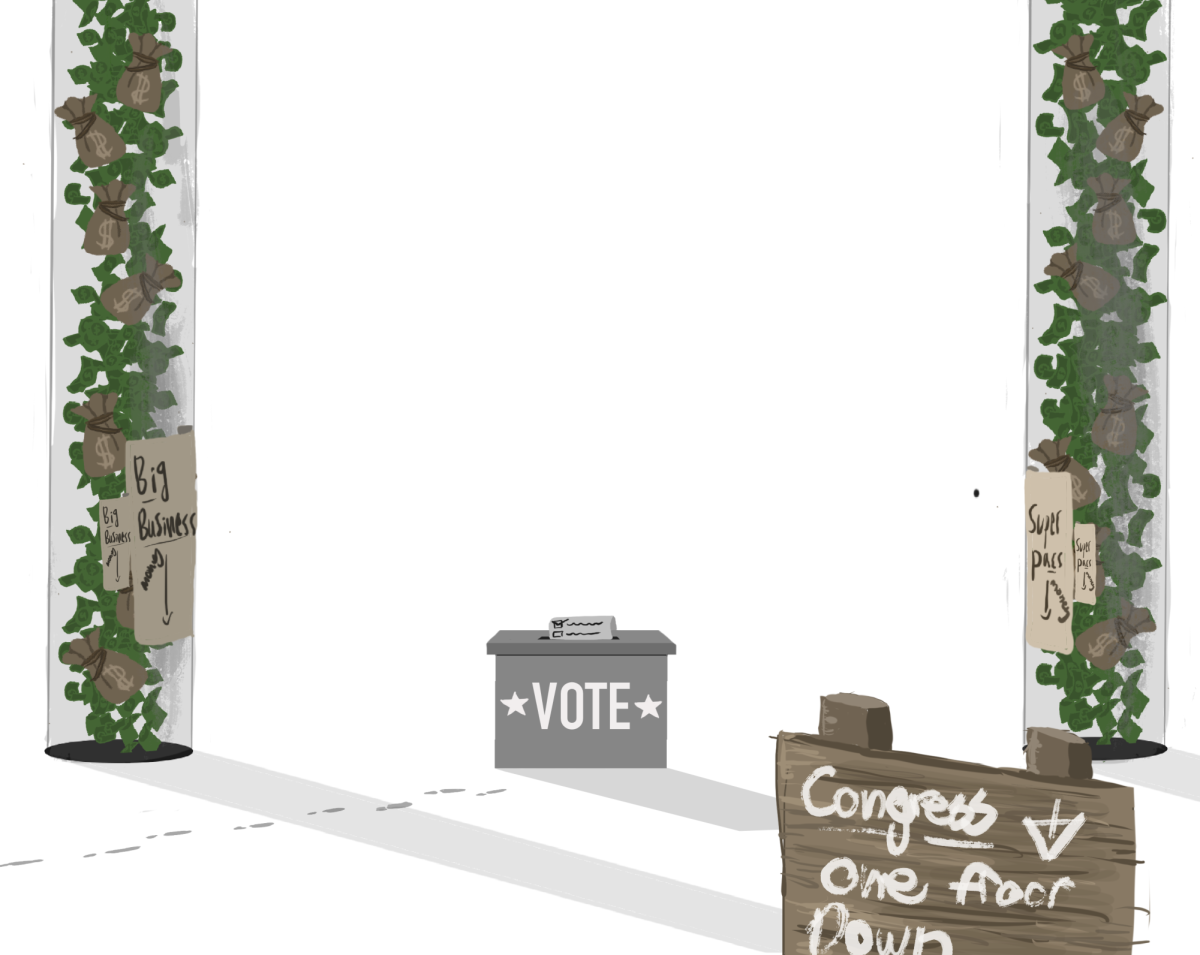

Is it American culture? The myth of “rugged individualism”, the curse of “boot strapping”? Who benefits when we drive ourselves to the point of breaking?

This piece causes me to contemplate individualism versus communalism and the real price of peace.

As a school counselor, I am begging anyone who experiences these challenges to meet with your counselor. We care about your humanity above all else.