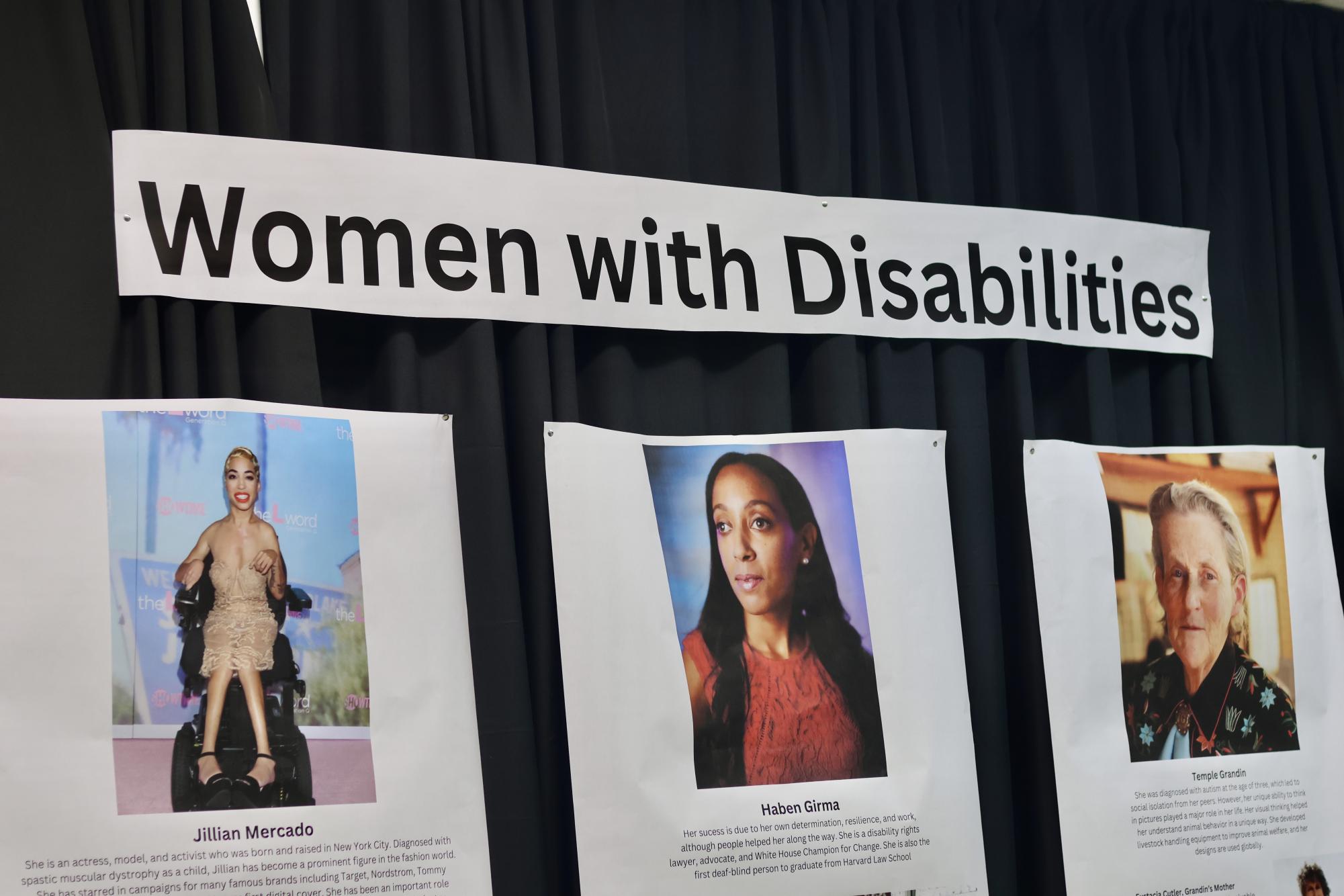

Haben Girma was the first deaf-blind person to graduate from Harvard Law School and is a lawyer and advocate for human rights along with disability justice.

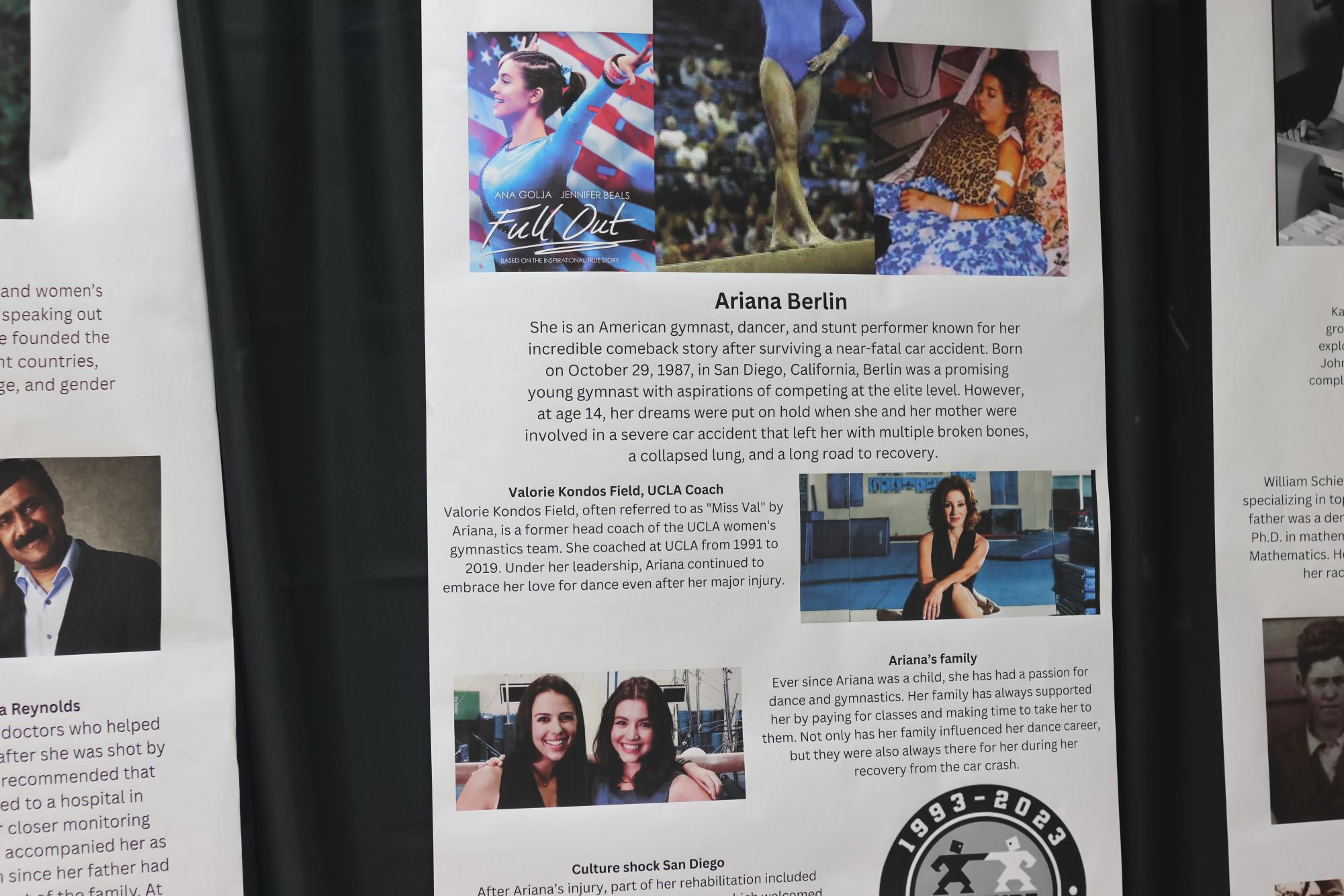

Climbing back to success after nearly being killed in a car accident that left her with several broken bones, a collapsed lung, and a five day coma, is Ariana Berlin, a gymnast, dancer, and stunt performer.

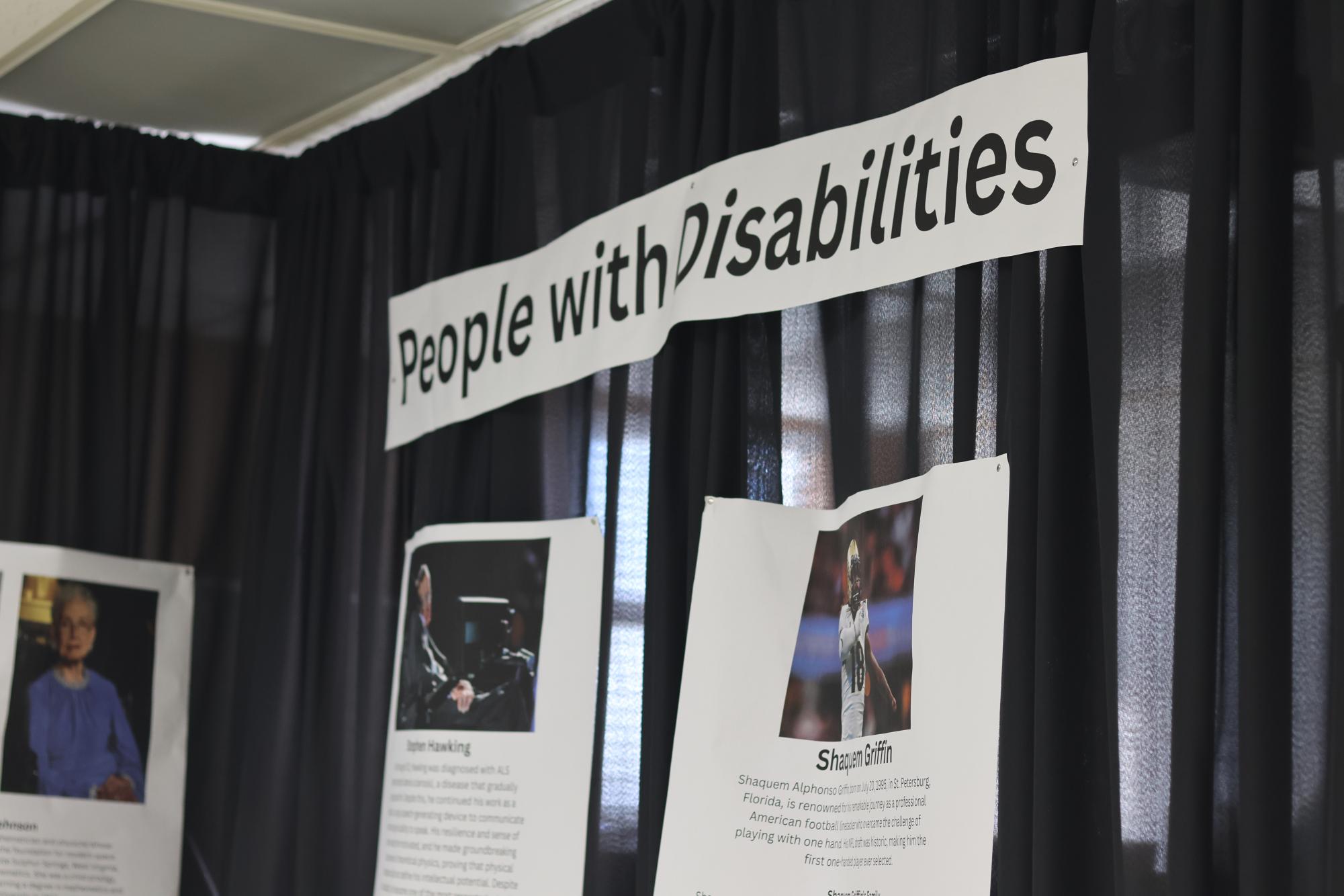

These are just a couple of the handful of women highlighted in room 138 for the “Together We Rise” Disability Awareness and Women’s History Month Exhibit, which recognizes a range of people with disabilities alongside remarkable women in society for the month of March.

With the help of the Leadership class, the exhibit was a “passion project” mainly spearheaded by senior Avari Brocker, president of the All Minds All Bodies Club, that focuses on cultivating a space to raise awareness about visible and invisible disabilities.

“As a young child who didn’t know that I was disabled and only knew that I was struggling, I felt really isolated,” Brocker said. “I felt like I didn’t have a community.”

Discovering her disability less than two years ago at 16, Brocker was inspired to find ways she could advocate immediately after being diagnosed with dyslexia and ADHD. Since then, she has become involved in the International Dyslexia Association and helps lead workshops in conferences as the president of the student empowerment group for the Oregon branch.

“Growing up like that made me realize that spreading awareness and education was part of my purpose in life,” she said. “One of the most accessible ways to do that here is by celebrating this month and making sure there’s exposure.”

The goal of the exhibit is not only to educate students and the local community about well-known or overlooked individuals with disabilities, but also to commemorate Women’s History Month with informational posters of inspirational figures.

“Recognizing both of those groups and the co-occurrence there was really important,” Brocker said.

Although there were some worries about what it would be like to combine Women’s History Month with Disability Awareness Month, she believed it could successfully be done in tandem.

“I don’t think that any group should have a lack of representation simply because we’re worried about minimizing the representation of another group,” she said. “We can all rise together.”

That’s why Brocker chose to highlight both months in one display.

“Representation of every variety, whether it’s gender, ethnicity, race or disability, is important,” she said.

According to Brocker, another part of the exhibit was recognizing the collective solidarity and support for people with disabilities.

“I think there’s a level of shame connected to having a disability and a reluctance to ask for help, because it feels like you’re not good enough,” she said. “But everybody needs help, everybody needs a village. Nobody gets anywhere on their own.”

While organizing the exhibition, she and the committee of Leadership students she worked with wanted to ensure that they showcased an equal representation of different groups.

“We tried to make sure that within this month, we’re also celebrating the diversity within this community,” she said. “Because it can affect people of all ages [and] backgrounds.”

But Brocker’s work with the school community didn’t end at the exhibit.

During Flex Time on Friday, March 14, students stayed in their homerooms to watch a video she helped put together that provided insight towards what the most common invisible disabilities were at school. ADHD, anxiety disorders, and dyslexia were among the most prevalent according to a study Brocker conducted for her club during Disability Awareness Month last year.

“We really just wanted to give people a window into what it’s like to be neurodivergent,” she said, adding how it can be difficult to explain the experience to someone who doesn’t encounter it personally.

Brocker also said that she hoped “it would help convey that emotional experience, because accommodations are very important, but understanding what it’s like to have a disability comes more down to the emotional aspect, because that’s the thing that doesn’t change with the accommodations.”

In her personal experience, she reflected on how it can also feel emotionally draining to have her struggles emphasized at school as a result of her accommodations.

Outside of school, Brocker said that sometimes her disability becomes more apparent in social situations too, but she’s thankful for friends who support her through the process, like when playing a game all together.

Between the exhibit and the video, there’s one thing she hopes for students to take away.

“Disability does not mean inability,” she said. “It also isn’t [a] weakness to ask for help.”

![Mr. Owen Furlong, the temporary Campus Safety Monitor, grew up near La Salle and described how Christ the King was “basically [his] backyard for a long time.”](https://lasallefalconer.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/115A2328-1200x800.jpeg)

Chris Babinec • Mar 20, 2025 at 11:40 am

I loved this exhibit and appreciate the coverage!

Avari’s assertion is so important: “I don’t think that any group should have a lack of representation simply because we’re worried about minimizing the representation of another group,” she said. “We can all rise together.”

So often, people sacrifice progress or won’t even start a piece of work because they are in search of perfection or purity. We are all interconnected and all have differences. Being in solidarity, being with each other, working with each other, joining in efforts matters. This exhibit and article captures that spirit.