Adele described motherhood well when she called it the “Sweetest Devotion,” and all parents should have the right to experience that devotion to the fullest. Unfortunately for most Americans, the time they deserve to spend with their newborn is often unaffordable.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) — of which the United States is a founding member — recommends that maternity leave should be no less than 14 weeks. Yet out of the 38 OECD member countries, the U.S. is the only one with no national paid parental leave (PPL) policy.

As it stands, the United States certainly doesn’t make parenthood easy.

The only form of PPL guaranteed by the U.S. government — the Federal Employee Paid Leave Act (FEPLA) — applies solely to federal employees and offers just 12 weeks of PPL, falling short of the recommended 14. It has several restrictions and isn’t stackable with the 12 unpaid weeks of leave provided by the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), meaning that workers who choose to take PPL through FEPLA must substitute it.

As an employee, if you haven’t worked at your current location for at least a year, good luck. If you’ve already taken leave that year, good luck. If you don’t work for a company with enough employees, good luck. And if you don’t work for the federal government at all — like 98.13% of the entire civilian workforce — good luck.

It’s just not enough.

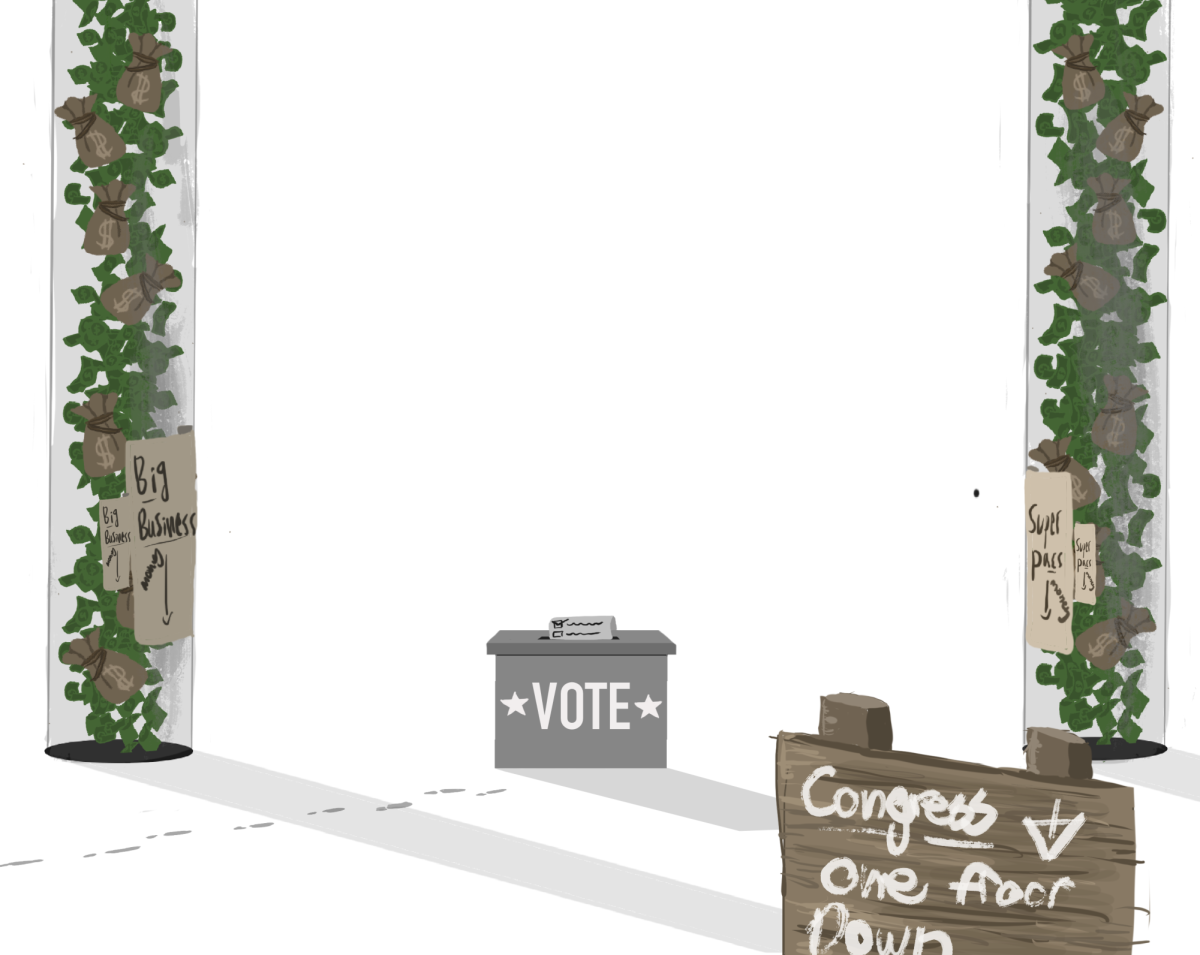

A few potential solutions to the problem — such as the Build Back Better bill and the The Family And Medical Insurance Leave (FAMILY) act — have been proposed and discussed extensively. But FAMILY has been introduced and reintroduced to Congress since 2013, and the Build Back Better bill was reduced into the Inflation Reduction Act, which does not address PPL in particular.

In 2022, a bill was proposed in the Senate that included a federal mandate of four weeks of PPL nationwide. Though the bill asked for less than the 12 weeks provided by FEPLA, it would have been a step in the right direction.

Evidently, that didn’t happen, as the United States is still one of only six countries worldwide not offering any form of national paid parental leave. It is also the only developed country not to, despite having a sufficient tax base to do so. Even if the bill had passed, it would still be an outlier, as out of the 186 countries granting paid leave for new parents, only one offers less than four weeks.

Fortunately for Oregonians, our state is a step ahead in terms of PPL with the implementation of the Paid Leave Oregon program. It mandates that employees can take up to 12 weeks paid leave for family, medical, or safe leave, and if pregnant, two more weeks can be taken for a total of 14 weeks.

It doesn’t have to be consecutive, either; as long as they take entire days or weeks, employees can choose when and how to take time off. While on leave, they still receive a percentage of their wages, and paid leave will also protect an employee’s job and role depending on individual circumstances.

Though Oregon has made amazing progress, the lack of PPL is a nationwide problem. The decision of whether to provide for parents is one that belongs to individual states, and only 13 states plus Washington, DC have enacted mandatory paid family leave systems. In an additional nine states, paid family leave may be provided through insurance, which not everyone can afford. And of the 23 total state leave laws, only 19 are currently in effect.

Paid parental leave isn’t something that should be left up to the state legislature, as evidenced by the 27 states that continue to neglect parents. Every parent should be able to bond with and care for their child without having to wonder if they can afford to eat and pay the bills, or if they’ll even have a job to return to.

Having a baby shouldn’t end either parent’s career, and a job shouldn’t have to come between parent and child.

Some may consider working from home to be a solution. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, in 2023, an average of 24.2% of mothers worked from home (teleworked) at some point in the prior week. But many jobs don’t offer the option to telework, meaning that lots of parents — both moms and dads — don’t have the option to stay home with their children.

Even for people who have access to it, the option to telework can’t fill the role of childcare. For the majority of parents, taking care of a child is a task as demanding and time-consuming as a career, and teleworking while parenting compounds the problem. You can’t expect someone to work two full-time jobs at once and do quality work in both.

Unfortunately, affordable childcare is often scarce. And post-COVID, the problem has only worsened.

Since February 2020, the number of employed mothers has increased by 1.9%. Contrarily, 63% of childcare centers and 27% of family childcare centers closed nationally during COVID, some permanently.

Childcare in America is an issue that the U.S. Department of the Treasury called “a crucial and underfunded part of the American economy” in a 2021 report. Though many childcare facilities reopened post-pandemic, the fact remains that affordable childcare is a rarity.

It’s no surprise that the turnover rate for childcare is so high when the pay is so inadequate.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, childcare workers are over twice as likely to live in poverty than workers in other sectors. Among the lowest wages of any occupation in America, childcare workers receive a median pay of $13.22 an hour. This is vastly disproportionate to the intense amount of work that must go into taking care of a young child.

Not only is childcare a demanding job, but it’s a task that requires a high level of quality, as workers have a massive influence over the kids’ development. It makes me nervous that they are paid so little when it’s so important that their work is done well.

The current funding system makes it even more difficult for disadvantaged parents to provide for their kids. In 2021, U.S. infant care prices cost single-parent households 24.6 to 75.1% of their family income, an obscene amount relative to the workers’ pay.

The network is primarily reliant on overburdened families and underpaid childcare workers, creating an inadequate supply of care for the families that need it most.

All those expenses pile up.

And finances definitely aren’t the end of baby complications. A new baby is a major upheaval not just of lifestyle, but of the way a woman experiences life. Often, changes and damages to a woman’s body are permanent, and the hormone imbalances cause emotional and physical instability.

The most fragile parts of the postpartum period — the acute and subacute phases — last about six to eight weeks, but that timeline is not one-size-fits all. And beyond those phases, there’s the delayed phase, which stretches from about six weeks postpartum to around six months postpartum. Again, that timeline is not all-encompassing. For many mothers, this recovery phase can stretch even further.

The mental effects of birth last much longer, and complications can arise in postpartum that may potentially delay the recovery period even more.

According to a 2014 study from the National Institutes of Health, the current PPL provided by FMLA — twelve weeks — “may not be sufficient for mothers at risk for or experiencing postpartum depression.” Postpartum mothers that had longer leave recovered their vitality and physical health better and showed a decrease in depressive symptoms.

But with bills to pay and an additional member of the family to take care of, for many new mothers — especially single ones — taking extended time off isn’t an option, no matter the physical and mental toll.

Plenty of parents have no choice but to work.

Mandating PPL could not only benefit mothers, but the economy as well. In 2023, the employment rate of mothers was almost 20% lower than that of fathers. Improving the U.S. care infrastructure could help alleviate these disruptions and allow more mothers to be employed, increasing labor force participation.

Estimates suggest that if the U.S. had a labor force participation rate comparable to Canada or Germany — countries that both have national paid leave and more comprehensive family care programs — the number of employed women would increase by about 5 million and generate over $775 billion for the economy per year.

Not only would it increase the number of working women, but it could expand the total workforce over time. Last year, the U.S. fertility rate reached a historic low, at an average of 1.6 births per woman. It’s the harsh reality that the choice to have a baby in today’s America is not a financially sensible one.

With a declining birth rate and an aging population, disaster looms for economic keystones like the Social Security program. Without enough young, working people to counterbalance the number of Social Security dependents, the existing system is unsustainable.

Building care infrastructure isn’t only the ethical choice; it’s the economically savvy one.

The decision on PPL isn’t one that should belong to individual states because its consequences don’t affect the states alone. The lack of proper parental and child care is a nationwide problem, influencing the entire workforce and economy.

If the United States cares about its future, it must first care for children. And if it cares for its children, it must first care for their parents — the moms, dads, and other guardians who often have to sacrifice so much valuable time and connection in order to provide for their kids.

If the United States cares about its future, it has to invest in its families.

Chris Babinec • Mar 7, 2025 at 9:30 am

Excellent, excellent, excellent. Salient points, support with data, this issue impacts every person in the country- whether they have kids or not. Thank you for this piece!