Ecuador was once regarded as one of the safest countries in South America. However, it is “an island of peace” — a term coined in 1991 by then-President Rodrigo Cevallos — no longer.

Recently, it has faced a seemingly unprecedented wave of violence that has caused a rapid descent into a “narco state under construction,” beginning with the escape of one of Ecuador’s most notorious gang leaders, the head of Los Choneros, José Adolfo Macías, also known by his alias “Fito.”

This escape prompted the government, led by current President Daniel Noboa, on Jan. 8, to declare a nationwide 60 day state of emergency which ended on April 7. This declaration in return sparked a wave of gang violence, most notably the hijacking of a television station during a live newscast in the port city, Guayaquil.

Due to this increase in gang activities, President Noboa took an extreme step by declaring an “internal armed conflict” and ordering Ecuador’s forces to neutralize the members of more than 20 gangs. This strong response made it seem like this was a one-time occurrence of public violence.

However, this was not the case, as in March and April, more extreme acts of violence took place. This included the murder of 27-year-old Brigitte Garcia, the mayor of the small town of San Vicente in the province of Manabi, who was found dead along with her associate Jairo Loornm in a car with gunshot wounds. She is not the only politician who has been killed in recent times, as just last year, presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio was gunned down at a rally by unknown assailants. Mr. Villavicenio was a harsh critic of the illegal drug industry, and his death can be seen as a turning point in the fight against drug cartels.

On Sunday, March 31, gunmen attacked a group of people in Guayaquil, killing nine and injuring 10 others.

One day later, 20 Ecuadorian gangsters abducted, interrogated and killed five tourists from a hotel in the beach town of Ayampe, thinking they were members of a rival gang.

Being Ecuadorian and having visited there as recently as June, it feels as if this dramatic shift came out of left field. However, there were cracks starting to show during my visit.

I was unable to see my family in Guayaquil because it was deemed unsafe by my grandparents due to its status as one of Ecuador’s major port cities, where a significant amount of drugs are shipped out of the country. One of my uncles also faced harassment from one of the local gangs in El Carmen, a town also located in the Manabi province, as they tried to recruit him. I also witnessed a traffic disruption due to a drug search by the military when visiting family at our farm in El Carmen.

Despite these occurrences, the lurking danger felt like a wave that would be dealt with just as quickly as it arose before turning into something permanent.

This was not the case — instead of the issues simmering down, they continued to rise after my visit until they culminated in the actions that happened in the beginning of this year and transformed the country into “unexpectedly becoming one of the most violent countries” in the world and, according to the United Nations, “a country under stress.” This is reflected in the homicide rate, which has increased from 6 per 100,000 in 2016, a figure comparable to the United States, to 40 per 100,000 in 2023.

So, how did this happen?

How did a country that just five years ago was named one of the safest in the world and one of the top locations for American retirees turn into a country ranked 11th most violent in the world alongside counties such as Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan?

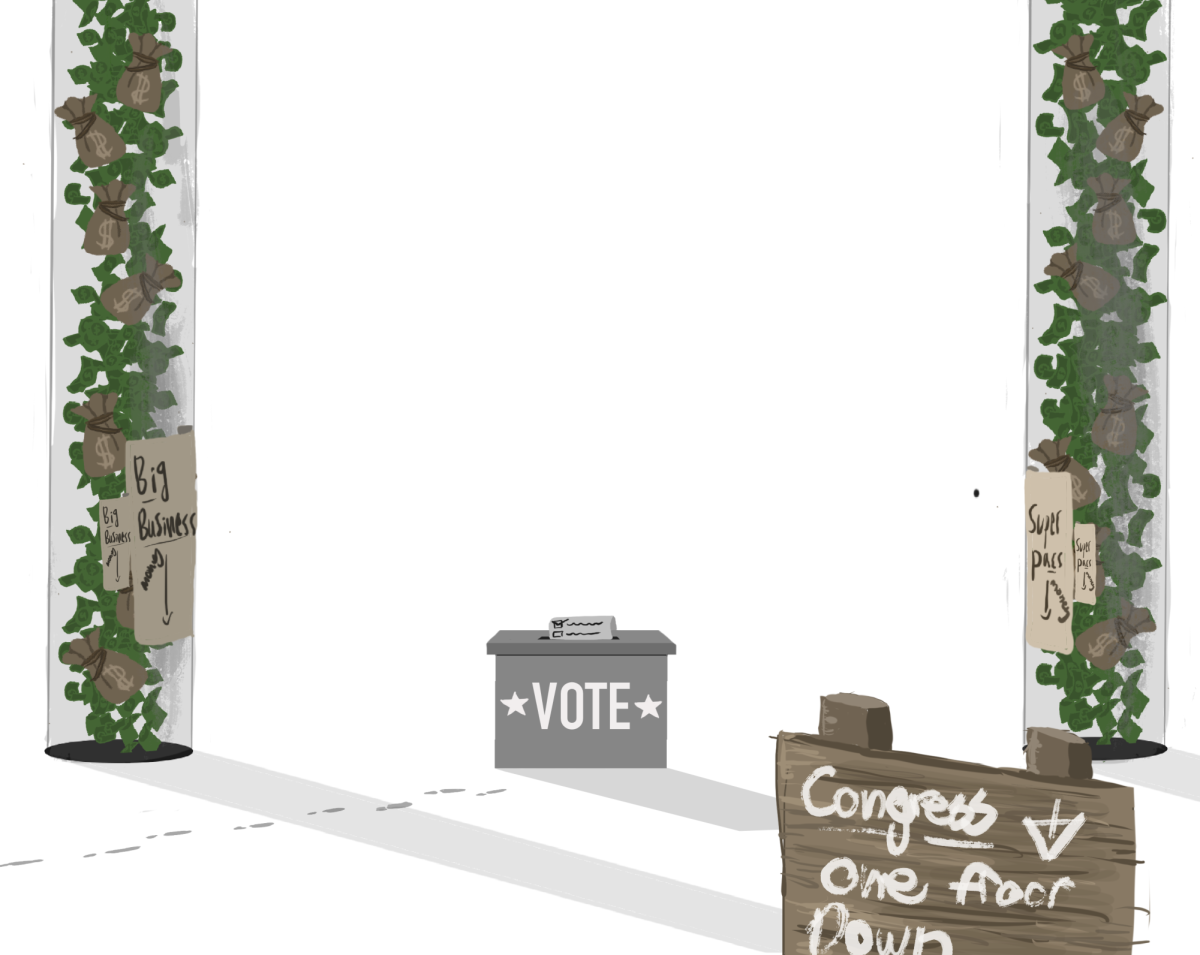

While the exact answer is very complex, simply put this violence and unease put forth by increased gang activities is due to an influx in drug trafficking, specifically cocaine, and government corruption.

But why in a continent racked with drug issues has Ecuador only now started to show signs of distress? The short answer: It hasn’t.

Ecuador’s issues have been building for a number of years, which most notably align with the crackdown of drug operations in Colombia. Ecuador is located right between Peru and Colombia, which are both regarded as two of the world’s top cocaine producers. However, beginning in the 2000s, “Plan Colombia,” a joint operation between Colombia and the U.S., was put into place to try to clamp down on the Colombian cocaine trade.

While this initiative may have helped stabilize the Colombian government, it didn’t actually treat its drug production issue and had the adverse effect of shifting cocaine transportation and gang operations to other South American countries, including Ecuador.

Ecuador has a nearly 1,400 mile coastline where drugs can be shipped from, and due to its title of the world’s top exporter for bananas, ships are constantly delivering the produce to different corners of the world, which is part of the appeal for why foreign gangs looked there for a new base of cocaine transportation, especially Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel.

The coastline and the major ports aren’t the only things that attracted attention of gangs towards Ecuador. The weak military and police response was another factor, as was the dollarization of the economy. For many years, Ecuador was shielded from the majority of the gang violence that has plagued the rest of South America. Thus, it was not equipped to entirely deal with this influx of activity and had not formed a strong police and military response to gangs, allowing for gangs to gain power rapidly.

The decision by former President Rafael Correa to shut down the American military base in Manta in 2008 was another factor. This military base was where American forces helped regulate drug trafficking in the Andean region, and shutting it down erased what little control there was, causing a dramatic growth in distribution. This was an election promise allegedly made to the FARC — a Colombian rebel group which, prior to its demobilization in 2017, was a large player in Colombia’s drug production and trafficking — in exchange for campaign financing. In 2020, Mr. Correa was convicted on corruption charges along with his then vice president Jorge Glas, who has been the subject of an international incident between Mexico and Ecuador recently for accepting $8 million dollars in bribes in exchange for public contracts, which helped “set up a network designed to smuggle drugs.”

But why does this matter?

As someone who this situation directly affects, it is hard to see a lack of attention brought to Ecuador’s decline. It almost feels as if the majority of people perceive this to be typical of a South American country, which in movies is synonymous with drugs and violence. I think it may also feel as if this gang activity is confined to the Southern Hemisphere. However, this is very far from the truth.

What happens in Ecuador doesn’t stay in Ecuador. The drugs are shipped to be sold in not just regional markets, but mainly foreign ones.

The increase in gang control should be alarming to Americans because besides Europeans, we are the ones playing a major role due to our large consumption of cocaine.

For the most part, Ecuadorians aren’t the ones using the drugs that are destabilizing the country; we are.

This also impacts the U.S., because the violence has been driving Ecuadorians to immigrate to the U.S. There has been a 368% increase in Ecuadorians arriving at the border from 2022 to 2023.

The violence that took place in January showed the extent that the gangs will go to keep their operations in place, because they know that the demand is only increasing. What is happening in Ecuador deserves attention; we can’t keep ignoring how ravaged this country is becoming and only pay attention when extreme acts take place.

For too long, Americans and Europeans have passively sat by, ignoring the pivotal role that they play in the mayhem occurring, but this year has shown that foreign countries can no longer sit by idly while their citizens are happily buying drugs manufactured and shipped from once-peaceful countries decimated by drug coups.

An example of the lack of engagement from the US that is hurting Ecuador is the failed arms deal proposed in March. This plan would have the United States empower its military by sending $200 million in weaponry in exchange for their Soviet-era technology. The U.S. then planned to send these weapons they received to Ukraine. When the Biden administration made this public, Ecuador was put in a tight spot as Russia — a top trading partner — imposed a ban on a series of key agricultural imports, mainly bananas, which was a devastating blow to the already weakened economy.

Ecuador called off the deal, but as one analyst put it, “the entire episode, from the country’s security crisis to the collapse of the weapons deal, exhibits the troubling consequences of U.S. inattention to its hemisphere.”

Ecuador is at the point where foreign involvement appears to be the only solution, because foreign interference has led to the current state of affairs. Simply put, America can’t be indifferent to the devolving from an “island of peace” to “a narco state under construction,” since its drug habit is what’s fueling it.

Bill Uicker • May 10, 2024 at 9:13 am

Thank you very much for this very informative article. I hadn’t heard about much of this, and I appreciate the author shining light on this subject. I hope through this attention we can encourage the development of solutions to this crisis and restore security and prosperity in Ecuador. Thank you!