The sight of a rolling tumbleweed is associated with the cliché that a place is desolate, barren, and unable to sustain life. As I entered White Swan on the Yakama Indian Reservation on Feb. 25, I was held by this stereotype as I saw a tumbleweed — as if on cue — roll along the road leading in and out of the town. But like tumbleweeds, which were only first introduced to North America by westward settlers, I was also a stranger.

As part of the first immersion trip La Salle has done to the Yakama Nation, I had the opportunity to do service on the reservation and surrounding area. As learned in the meetings preparing us for the immersion, we were not coming in with the expectation of making an immediate or tangible impact on systemic issues at large; there is only so much a week can allow.

Willow Howard, the sole member of the Yakama Nation Governmental Affairs Liaison, came to speak to the group for about an hour in our first days on the reservation. In that time, she was able to lay out the experiences of life on the reservation and of the Yakama Nation since its establishment.

Signed with 14 X’s — in place of names — by delegates of the tribes and bands of the region, the Treaty of 1855 created the federally recognized reservation, giving way to most of present-day Washington and Oregon to settlers. Under the treaty, the document promised the Yakama exclusive use of more than a million acres of land in south central Washington and the authority to govern itself.

Today, the Yakama’s lifeblood is dammed. The migration of fishes has been restricted or otherwise blocked by several dams — including some that provide hydroelectric power to the Portland area — on the Columbia River and other structures on its tributary waterways.

Howard said that one of her goals is to have salmon on the table and salmon in the river. In addition to other ecological issues, the Yakama calendar start of the new year, which coincides with the harvest of xásya, wild celery, had to be moved up by a month to February due to climate change, she explained.

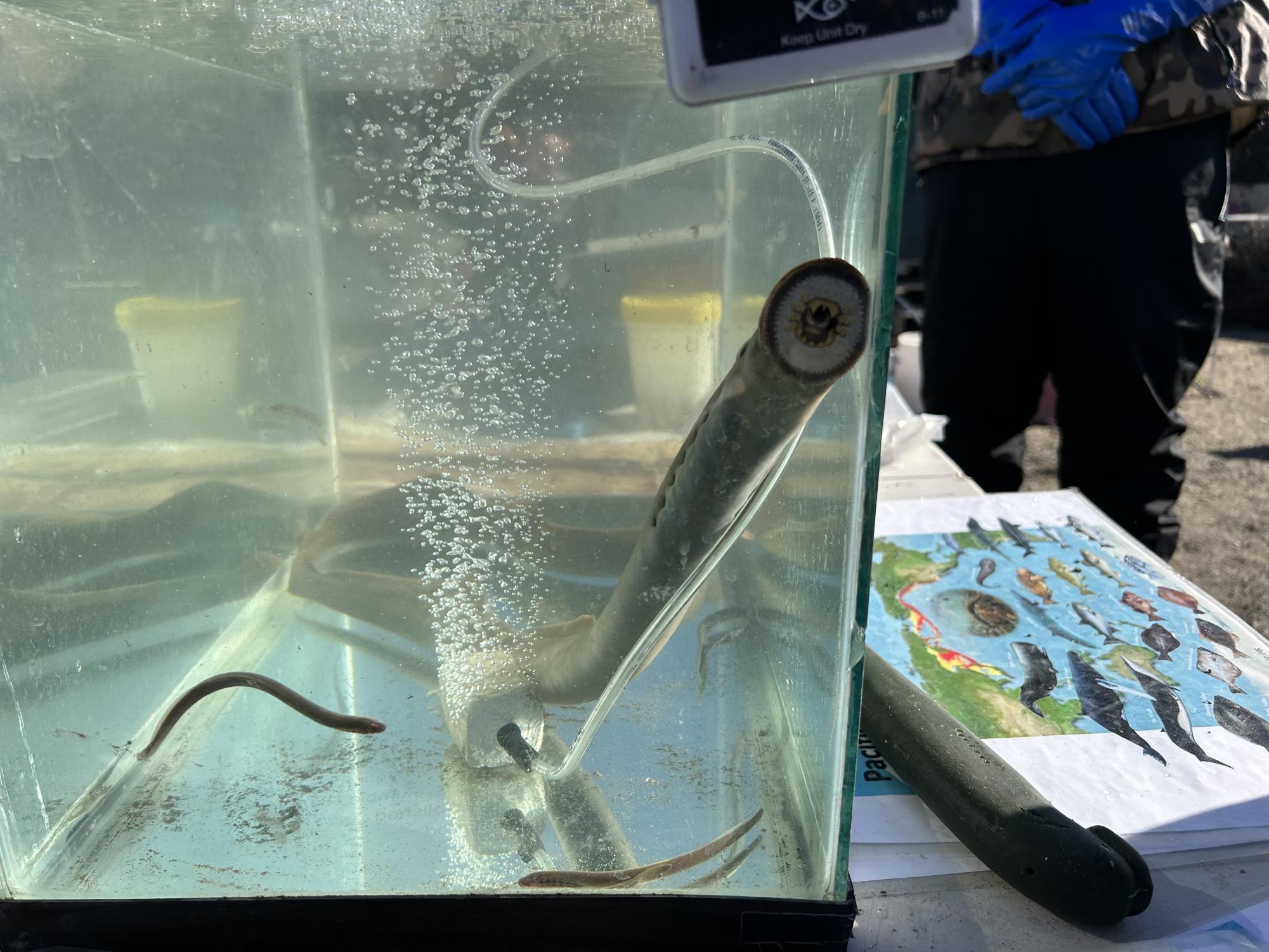

For two days at the Prosser Hatchery, tended to lampreys, a species of fish that feeds by latching onto its prey and is valued by the Yakama as one of the first foods. The importance of these first foods originated with the story that animals would volunteer themselves to the tribal people in exchange for being the animals’ stewards.

The hatchery was equipped for visitors such as immersion groups, holding tanks full of novel specimens including albino and conjoined salmon. While elbow-deep in lamprey waste, it may be hard to recognize the significance of the lamprey, but as dams, climate change, and other factors threaten Yakama culture, the spawning of these fish represents the continuance of the Yakama’s way of life despite the pressures of a changing world.

Fishing and farming are staples of the reservation’s economy. Miles of out-of-season fields used to grow hops — a key ingredient in the production of beer — lined the roads of the reservation. None are owned by enrolled tribal members, according to Howard. When the reservation was established, representatives of the Yakama Nation had expressly outlined the ban on alcohol with the hope of minimizing the effects of “ardent spirits.” The reservation is distinct as being one of a few tribally owned casinos in the U.S. to not serve alcohol.

It’s known as a checkerboard reservation, meaning that the tribal land of the government is also occupied by non-native owners. However, this would also allow some of the first Filipino Americans to establish themselves despite Washington law at one point restricting their ownership of land.

The lands of the Yakama have been a host for the hopes of newcomers, such as Mike Sauer. Coming to the Yakima Valley about 55 years ago and a parishioner of St. Mary’s church since then, he invited our group to visit his vineyard a few miles outside of White Swan after seeing us at Wednesday morning mass.

Sauer had started the vineyard when he married into his late wife’s family and has since produced some of Washington’s most acclaimed wines under the Red Willow label, however, he explained that he walks with humility with his relationship with the Yakama.

Sorting through donated clothes and juvenile lamprey, the issues faced on the Yakama Indian Reservation are not isolated, as Howard pointed out that many of the issues that Native Americans face are shared by reservations across the U.S.

Going on an immersion trip, you aren’t expected to fix or even fully understand the full scope of what a group has experienced, but the best way to learn is to simply be there. This was made clear to me on the application form, to not be a tourist. Yet, so many of the issues are foreign but not distant.

To know that these problems are much larger than what a group of high school students and a chaperone can fix — at least immediately — is a humbling experience. It is our privilege to come and go as we please. But service shouldn’t end there.

As land acknowledgements become more prevalent before events in an attempt to acknowledge and respect the indigenous inhabitants whose lands we occupy, their names are more than just gestures but a reminder that they are still among us.

While verbal, it is this type of awareness that allows us to recognize our privilege. More than just sympathy or charity, it is with empathy and recognition that we can begin to address the issues that a group experiences and our role as part of the solution.

Tom McLaughlin • Mar 27, 2024 at 11:29 am

Beautifully written reflection, John. Thank you for serving our community by attending this immersion and offering service to the Yakama Nation. The issues are so complex, especially for being rooted in a devastating and painful history of encounter with the colonizing nation of the United States. Solutions to ongoing issues are possible when we exercise our will to heal the wounds initially inflicted by some of our ancestors. Thank you for shining light on this opportunity for healing and growth, for the potential for fruitful relationship with each other and the land.