From boulders and greenery placed in otherwise vacant and open spaces, to park benches with armrests spaced out for a single person, to conspicuously placed spikes dotting raised or covered surfaces, if you’ve explored Portland, you’ve seen it.

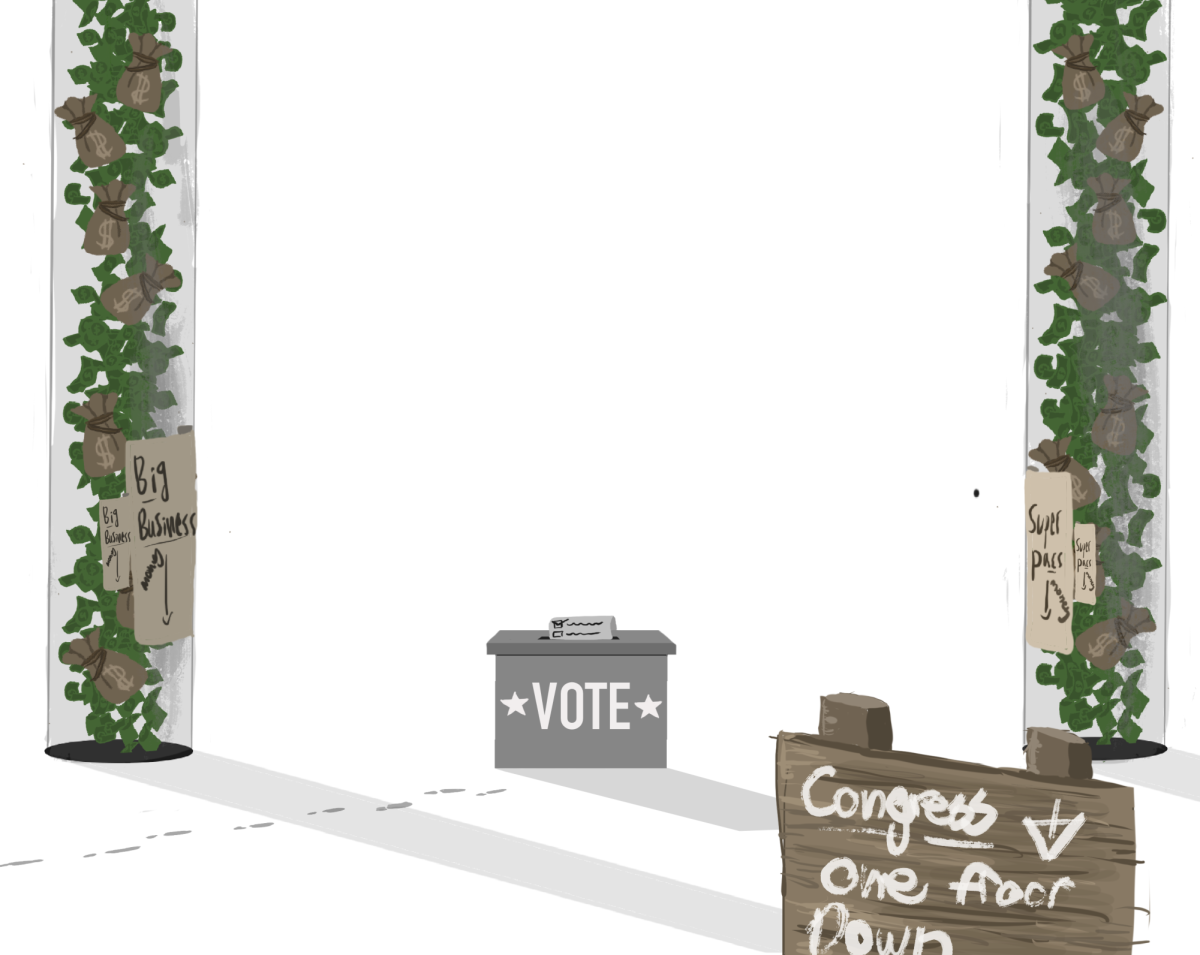

Hostile architecture — urban design that incorporates details to intentionally stop unwanted behavior — has been popping up all across many major cities within the U.S. for the past decade. Streets, public parks, underpasses, and many other spaces previously taken up by tents and makeshift shelters have now been transformed into completely uninhabitable environments.

As the homelessness crisis has become more and more apparent in Portland, with a 65% increase in the number of those on the streets in the city, so has the funding for the construction of defensive architecture in many public spaces. Last February, the Portland City Council spent $500,000 on the installation of benches and other structures intended to deter anyone from staying near Laurelhurst Park and other public spaces.

A few years prior in 2019, the Oregon Department of Transportation spent over $800,000 on the placement of boulders at five previous campsites, where the tents of many houseless residents could be found.

The main intent of these structures and installations was to move campers away from these areas, and keep them away.

This practice is not only ignorant and lacking in empathy, but is simply a deterrent and not a solution. Hostile architecture further worsens and embodies the stigma and prejudice the houseless face, all while the houseless population continues to rise.

The use of hostile architecture and urban design has become an increasingly common tactic in the attempt to move camping sites away from the general public and busy locations that could potentially lead to accidents, but has in turn increased the displacement of the houseless community.

Moreover, amidst the escalating housing crisis and the growing calls for action on behalf of both the houseless community and the strain on the communities where they seek refuge, the city of Portland finds itself unable to meet the increasing demands. Even after having spent $1.7 billion on humanitarian services and affordable housing, far too many people seeking humanitarian aid, temporary shelter, and affordable housing are put onto waitlists lasting up to five years.

This crisis affecting thousands of people is in dire need of real and long-term solutions, and hostile architecture is not the answer. It is simply punishing the houseless for having nowhere to go.

No one wants to sleep on the streets, and by ousting and displacing those who have no alternative, we are making their lives even more difficult because those with the power to put proper solutions in place chose to not address the root of the problem and instead only seek immediate solutions which merely benefit aesthetics.

Continuing to treat this situation with temporary and dehumanizing solutions will only create further problems down the line. We are using funding to move them from one unwelcoming space to another unwelcoming space, rather than using it to provide more shelters, affordable housing, and aiding resources.

Instead of funding discriminatory urban design, our government needs to focus more on policy reforms and social services. This could be implementing regulations prohibiting or discouraging the use of hostile architecture and instead directing that funding into social services such as affordable housing, accessible addiction treatment programs, and mental health services.

The houselessness crisis is far too deep of a wound to use Band-Aids. We need long-lasting solutions that benefit both the public and the thousands of people barely getting by on the streets.

This is not merely a public safety hazard, nor a drug crisis, but at its core, a humanitarian emergency that cannot simply be pushed away by boulders and benches.