Welcome to the fourth edition of Stick a Fork In It, the column where we explore the foods that La Salle loves. Each week’s edition features a different dish volunteered by La Salle’s students and staff.

This week’s dish is sophomore Amalia Hinchliffe’s pastitsio, the first savory food covered by this column. This Greek classic, a beloved pasta dish made with creamy béchamel (white sauce), beef, and tubular macaroni, is similar to an Italian baked ziti or lasagna.

Though this year Hinchliffe’s family made the dish for Thanksgiving, her grandmother used to make pastitsio for their family every Christmas. It became a tradition in their family to make it every year because it’s Hinchliffe’s favorite dish — she rates it a 10/10. “My grandma would always make it for me, and she’d be like, ‘Amalia, I got your favorite dish right here!’ So that was just nice,” Hinchliffe said.

Carrying on the tradition, Hinchliffe and her cousins make the traditional pastitsio every Christmas. She said that they try to make it every Thanksgiving as well, but they don’t always see each other because her cousins live out-of-state.

They make it with the help of Hinchliffe’s aunt. “She’s trying to teach the new generation, so she’s trying not to help us as much,” Hinchliffe said, laughing.

The modern pastitsio was developed by Nikolaos Tselementes, a French-trained Greek chef of the early 20th century. In the context of that time and with the influence of Western trends and political circumstances, he wanted to distance Greek cuisine from Turkey. Therefore, he introduced French, Italian, and Western styles of cooking.

The Italian dish that was the main influence of pastitsio is called Pasticcio di Maccheroni. The word pastitsio comes from the Italian word “pasticcio,” meaning pie. Over time, it has also gained the figurative meaning for “a mess.”

There are versions of pastitsio all over the Middle East. In Cyprus, one can find “makarónia tou foúrnou,” which means “baked macaroni,” and in Egypt, there is version called “مكرونه بشمل,” or “makarōna bashamel” in Egyptian Arabic, or “macaroni béchamel.” In Southern Europe, there is a version called “timpana” in the country of Malta, and in The Balkans, there’s “pastiçe.”

Before Tselementes invented the modern version, pastitsio in Greece had a filling of pasta, liver, meat, eggs, and cheese, and did not include bechamel.

Tselementes’ version — now ubiquitous — has a bottom layer that is bucatini or other tubular pasta, with cheese or egg as a binder and a middle layer of ground beef (or a mix of ground beef and ground pork) with tomato sauce, cinnamon, and cloves. The top layer is a béchamel or a mornay sauce. Hinchliffe’s family uses béchamel sauce for their pastitsio.

Pastitsio takes a lot of time and effort to make, so Hinchliffe rated it at a 7/10 for difficulty. It’s the beef and the béchamel sauce that are the most time-consuming to prepare, and the béchamel sauce in particular is a tricky business. The eggs in the sauce curdle very easily, so one has to be careful when making it.

Egg curdling is when raw egg is put into a hot mixture, and the egg begins to scramble. In order to avoid that, Hinchliffe suggests completely mixing the egg with a small amount of the hot liquid before combining it with the rest.

“Don’t be a victim of the curdle,” Hinchliffe said.

Despite the difficulty, béchamel is a necessary ingredient for pastitsio. In January 2019, the New York Times made an apparently erroneous Facebook post of a “pastitsio” recipe which sparked a lot of anger amongst the Greeks that viewed it. A chief complaint was that the recipe did not include béchamel sauce — therefore, it was not considered real pastitsio at all, but was more like a baked ziti. The commenters, many of them Greek themselves, angrily asserted that this dish, whatever it was, should be given a different name.

This Thanksgiving, Hinchliffe’s family made the béchamel sauce with cashew milk, because her mother is lactose intolerant. First, one places the cashews in hot water for ten minutes, then blends equal parts cashews and water to make cashew milk. “I didn’t know that’s how you make cashew milk, and I thought it was pretty cool,” Hinchliffe said.

Hinchliffe’s family mainly eats pastitsio at home, but once every year, they may be able to buy it at the Portland Greek Festival. The annual event, held this past year in the first week of October, is a celebration of Greek culture run by several Greek Orthodox Churches in the Portland area, and it features Greek food for sale and Greek items for auction.

“There really aren’t a lot of good Greek restaurants in Oregon,” Hinchliffe said. “So everybody comes to this Greek festival. They don’t do any advertising for it, but so many people are there. This year was the first year where we basically ran out of everything.”

Pastitsio reminds Hinchliffe of “that Christmas spirit, and my grandma and I,” she said. It represents the time she spent with her grandmother making the dish when she was younger, and now, the time she spends with her aunt and cousins learning how to carry on the family tradition.

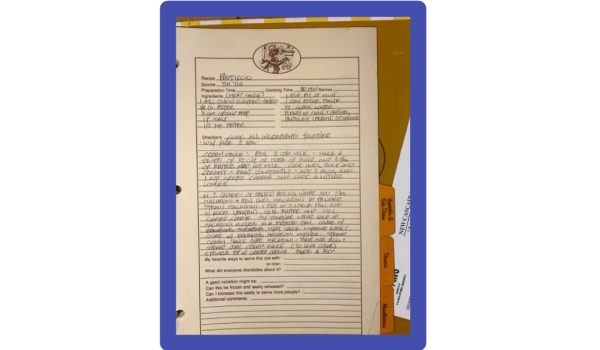

If you would like to try making pastitsio, this is the recipe that Hinchliffe’s family uses!

A typed version of the recipe is also included here.

—

If you would like to volunteer a dish of your own, this is the link! All we will need from you is a brief interview about your personal history with the dish and a recipe. Signups are open to La Salle students and staff alike.