I am Native American.

However, according to the Colorado River Indian Tribe, I’m not, because of the amount of “Indian blood” I have.

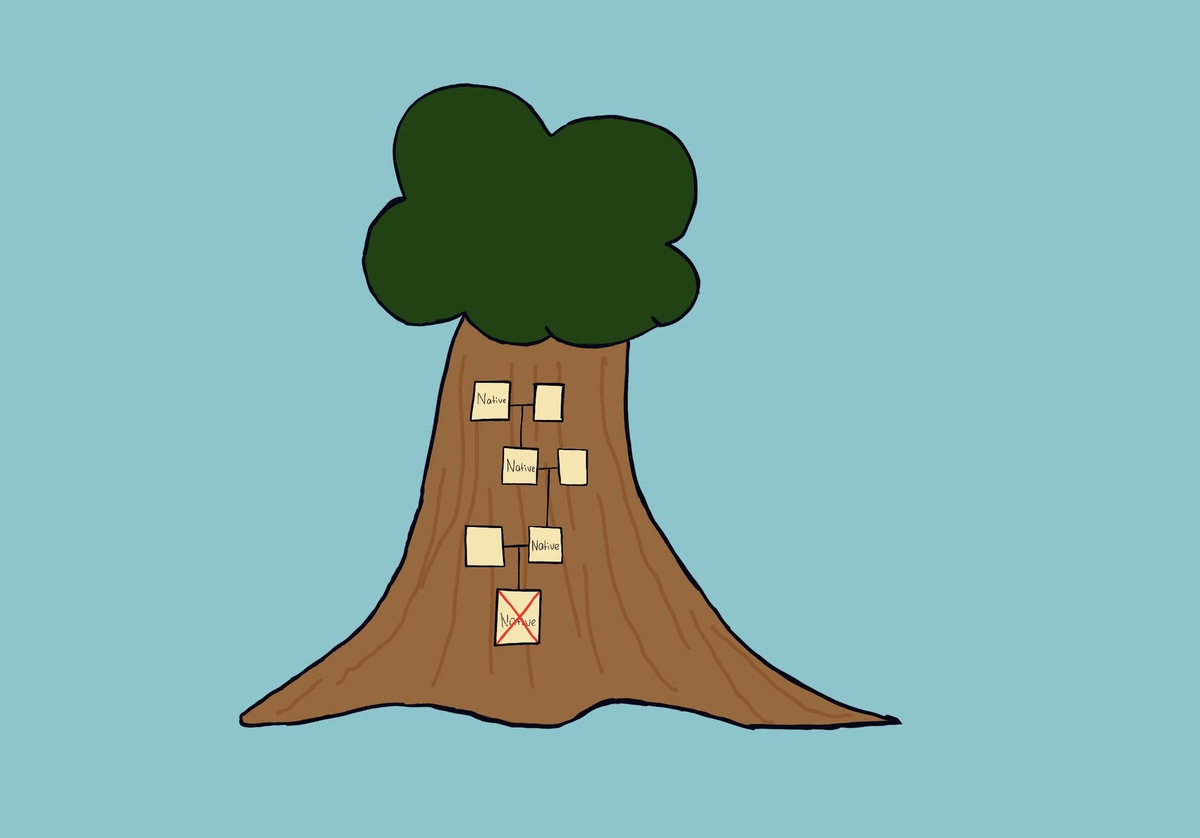

To be enrolled into the Colorado River Indian Tribe, like my dad and the rest of his family, I have to have enough “Indian blood.” The concept of “Indian blood” comes from blood quantum, which is a fraction of someone’s “Indian blood” that is calculated from an individual’s family tree. This idea to use blood quantum and “Indian blood” came from white settlers.

Blood quantum was imposed on tribes by the government in hopes of keeping the tribes smaller and excluding “fake” Natives, or those who don’t meet the amount of “Indian blood” needed. The amount of blood quantum needed differs from tribe to tribe, as there is no standard amount across the U.S.

My family tree contains three main tribes: the Mojave, the Creek, and the Kiowa. I’ve grown up hearing about these tribes — stories of all of my family still on the reservation down in Arizona, and family in New Mexico from my great-grandma before she moved to the reservation.

As I’ve gotten older, I have become more curious about my Native heritage through learning more about my great grandma’s side of the family, as she is one-half Creek and one-fourth Kiowa in blood quantum.

The fractions obtained from blood quantum do not specifically come from DNA, as one would think; it’s actually more of a math equation. The government used a collection of tribal documents and went back to an originally enrolled member who had full blood, basing qualification for future enrollments on descendants of that member, whose blood quantum reduce with every generation. This system is still in use today, with the tribes now in charge of the blood quantum process.

One problem is that there is no certainty that the original members had full blood. The members of the tribe who were counted as having full blood were based on how they looked and how involved they were with the tribe. Since full blood was decided based on looks, people of mixed heritages can be considered full blood members.

From a young age, I’ve always felt connected to my Native American background. I grew up seeing homemade Native dolls in my grandma’s house, being told stories about my great-grandma’s childhood, and being given jewelry made by my great-great-grandma.

When asked about heritage, the first thing I’ve always acknowledged is my Native background. It’s always been a source of pride for me.

For many years, in middle school and even now in high school, whenever we were asked to do a project about a Native American tribe, I always chose mine. I wanted to learn more about them and share the culture with my class. They were always my favorite presentations to do.

Since I do not have enough “Indian blood,” I cannot enroll into the Colorado River Indian Tribe — the tribe everyone in my family is a part of, the tribe I know all about, and the tribe that I should call my tribe. Along with missing out on benefits from the tribe, such as a yearly check and tuition for school, I also miss out on having a greater community of people and mentors who come from the same background.

Blood quantum makes it difficult to feel connected to my own culture despite the fact that I’ve grown up around it. I am the oldest great-grandchild, meaning I am the first in the family to not be able to enroll in the tribe, and none of my other cousins will be able to do so either. This means that one day I’ll be the one to pass down our culture to others, even though I am not a part of the tribe.

As the tribes are in charge of the amount of blood quantum, it is up to them now to remove the blood quantum system in order to allow the culture of their tribes to stay intact in the future. I understand the fear of allowing too many people into the tribe and having them take advantage of the benefits, as many tribes cite this as the reason they keep the system. However, with advancements in technology, it is very possible to use DNA percentages for the blood quantum. The current system for blood quantum of using old documents — that are possibly incorrect — needs to be phased out.

Tom McLaughlin • Nov 30, 2023 at 1:34 pm

Thank you, Maddy, for your thoughtful essay. I can hear your love and pride for your Colorado River culture. I feel sadness and frustration that a federal policy from long ago continues to cause harm generations later to you, your cousins, and countless other people. Despite this, your commitment to honor and pass on your culture to the next generation of your family and friends inspires me!