American Education: Where Mental Health and Grading Collide

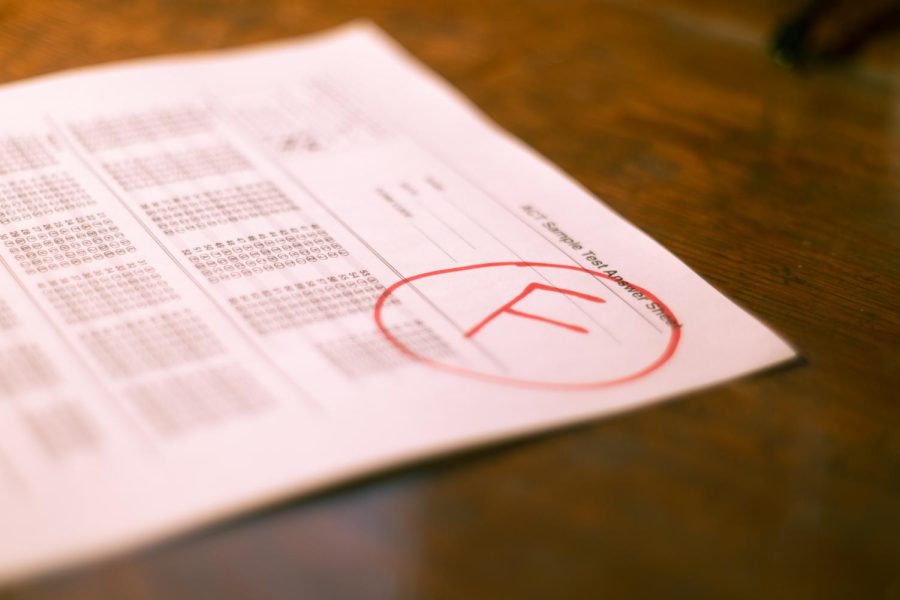

While receiving low grades can significantly impact students’ mental health, they’re often viewed as a necessary part of the school experience.

March 2, 2022

Ever since the foundation of modern American education by Horace Mann in 1837, our system of grading and schooling — despite groundbreaking developments like desegregation and standardized testing — has remained fundamentally similar over time.

At La Salle, there are a variety of thoughts on this issue, from satisfaction to a desire for total reform.

“Our education system is antiquated,” religion teacher Mr. Tom McLaughlin said. Some Lasallians agree, while others view the current system as both functional and effective at promoting growth.

In the past decade, there has been greater public pressure to reevaluate education to meet the needs of the complex modern world. Just recently, more than 40 New York public schools have made wide-sweeping changes in a grassroots effort to reform education by removing grades and giving students indefinite time to learn the curriculum.

While different teachers at La Salle have broad opinions, a general dissatisfaction towards the hyper-focus on grades is an opinion several teachers share.

“Anecdotally, it sure seems like people are a lot more concerned about grades for the grades’ sake,” science teacher Mr. Kyle Voge said. Others, like English teacher Mr. Gregory Larson, echoed this message, noting that our culture often emphasizes grades above all else.

“They would read the [feedback], but they wanted points,” Mr. Larson said. “I don’t blame them.”

While teachers view grades as a legitimate part of the school experience, some find the cultural focus on academic success damaging. English teacher Mr. Christopher Krantz, for instance, even finds it “sick,” specifically regarding platforms like PowerSchool, which give immediate access to a student’s grades. Teachers like Mr. Larson and Mr. Krantz see this instant access, while convenient, as often emotionally damaging.

Mr. Larson feels the constant access to grades supports and strengthens the obsession with grades. “I remember asking teachers about content because I wondered, because I didn’t understand something,” he said. “Now students are coming to talk to me because of their score. And they see the problem as a problem with their score, not a problem with understanding, or they don’t see this connection between their score and their level of understanding.”

Despite the general consensus that there is a problem relating to PowerSchool, there is disagreement on the scope and severity of the issue. Some believe that while PowerSchool can become a distraction, it is helpful for a parent to access their child’s grades at any time. “I think that if I were a parent, or a student, or the school, I would like to be able to just check on how they’re doing at any given time,” Mr. Voge said.

While students with lower grades are often those with the most potential to grow, Mr. Larson said, an unhealthy psychological relationship with grades can cause students to shut down before they have a chance to succeed. “It shouldn’t be about how do I get that number in PowerSchool up,” science teacher Mr. Ryan Kain said, “It should be about learning. It should be about understanding.”

As one strategy to combat grades as a toxic distraction from learning, Mr. Larson has students read and respond to constructive critique first and receive their grade afterward. According to Mr. Larson, the intense emotional reactions students have towards their grades often prevent them from productively internalizing feedback, so prioritizing commentary on their work over the final letter grade can emphasize learning in a healthy way.

“It took me a bit to accept it, and understand that I have to put in extra effort if I want to get a good grade on an assignment,” freshman Kayla Chapman said about Mr. Larson’s grading techniques. “There is a lot of feedback on almost every assignment, and it is very detailed.”

Another way to approach the issue of grades is through more interactive learning. While lecturing can be helpful, “it’s passive learning,” design thinking teacher Ms. Carie Coleman said. To get students more engaged, she said that it is often necessary to learn as a group. This way, more engaged students might be able to look past the points and more towards their innate curiosity.

“Her feedback is really helpful and moves you forward in the thinking process,” freshman Phoebe Sandholm said about her involvement in Intro to Design Thinking and Tools.

While some students want to branch off on their own, Ms. Coleman also practices alongside students with tools such as models. By segmenting groups of students into different pathways, it allows other students to work at different paces while increasing classroom engagement.

Another strategy mentioned by Ms. Coleman is the 16 Habits of Mind, which have helped her during the pandemic. “During the pandemic, I’ve been really trying to focus on is habits of mind and what they are,” she said. “It’s not about content, it’s about habits.” This strategy is another cornerstone of her classroom environment which she says bolsters individual problem-solving skills.

Through increased engagement with the curriculum, it can instill genuine curiosity rather than dutifully working towards the highest grade, as pointed out by teachers like Mr. Larson, Mr. Krantz, and Ms. Coleman. But “it takes a long time to turn a boat,” Mr. Larson said. “I hope it’s not the Titanic, but we’re on a large ship.”

Focusing on using grades as a method to display understanding intentionally and mindfully can give students opportunities to show their understanding. Directly talking about understanding and its relation to grades, as Mr. Larson commented, is one way to establish this connection. Another, Mr. Kain said, is to be critical and thoughtful about how different assignments and grades are weighted.

Mr. Kain also tries to adjust what counts towards a summative grade, or a grade meant to summarize total learning, rather than simple practice. “If it’s all tests, that’s not necessarily a demonstration of understanding, because there are different levels of capabilities taking tests,” he said.

Altering what counts towards summative grades also incentivizes students to genuinely internalize critical concepts rather than simply “go through the motions,” Mr. Kain said.

Although some teachers at La Salle acknowledge that grading can limit intellectual risk-taking and have developed many different practical approaches to the issue, there are varying opinions on how our society should approach grading systemically and philosophically.

Some teachers find that grades effectively demonstrate whether or not a student is hitting the mark. When grades are given fairly and honestly, they can convey invaluable life lessons.

While poor grades can be painful, failing can be “part of developing resilience,” English teacher Mr. Krantz said. “The world will not end.” Mr. Krantz thinks that without failure, students will be unable to deal with the much larger crises later in adulthood.

As he said in an anecdote about his daughter, Mr. Krantz remarked on how, after feeling devastated by a B grade on her math test, she learned how to “deal with the challenges associated with not always producing stellar work.” Moreover, handing out high grades for little work in return, Mr. Krantz said, does not benefit the student.

“Authentic success comes from authentic work,” he said. “Pretty much anything worth doing in the world is going to require hard work.”

This said, Mr. Krantz still has “mixed feelings” about grades. Despite their ability to build resilience, Mr. Krantz believes grades can contribute to mental health problems if students define themselves too much by their grades. Moreover, Mr. Larson believes that if feedback is delivered incorrectly, it can actually deter someone from authentic academic growth.

Ms. Coughran, the Vice Principal for Academics, has a more positive view of the grading system. “We have quality curriculum and quality teachers,” she said, agreeing that grades can serve to incentivize growth and quality work. “If they’re able to persevere and understand why they got their grade and make some habit of mind changes, I think that’s where the learning is really going to happen,” she said.

But instilling those attitude changes can be difficult, and “we don’t have a good way of doing that right now,” Ms. Coughran said. “I think teachers do a good job individually in their classrooms and talking about habits and what’s going to make you successful in my class. But as a holistic approach as a school, I don’t think we are there yet.”

The pandemic has magnified some of these issues in ways that fundamentally changed schooling and the relationship between teacher and student. “Last year we had to be extremely sensitive to the mental health of students to not overburden them,” Krantz said. “This year too, though, we’re still in [COVID-19] and we’re still dealing with the need to be sensitive.”

But, Mr. Krantz added, “part of their welfare is their success in life.” Although the health of his students is his “number one priority,” he said, there is still the need to push his students to create the best work possible.

The science department had its own necessary changes as well. “[My classes] are becoming less content-based and more skill-based,” Mr. Kain said. “The most important thing I can teach my students in a science class are those science skills.” A big part of this was less time to work with students directly. “Everything takes longer in a digital space,” Mr. Kain said. Although digital learning has ended, some of these alterations have bled over into 2022, he said.

Another topic where educators have different approaches is grade inflation, or rewarding higher grades and consequently increasing the average GPA.

On one hand, Ms. Coughran believes that “we want to give students the benefit of the doubt. We want to help them be successful and we know they’re facing a lot right now.” Inflation, Ms. Coughran said, is a “product of education,” and doesn’t necessarily see it as a problem in dire need of reform. However, she does think it happens “in all schools.”

Others say that letting students fail and learn to persevere is exactly what will allow them to be successful. “There’s this over-prioritization of the immediate,” Mr. Larson said. “We feel that grading is a loss of points. I would love for school to be a gaining of knowledge.”

Mr. Krantz said that grade inflation is “a big issue everywhere. Everywhere. Huge.”

Though grades are important to both students and teachers, it’s “just one piece of a bigger system,” Mr. Mac said.

The “college industrial complex,” as Ms. Coleman calls it, has become more competitive in recent years. While the reason for this change is unclear, stress and anxiety have torn through younger generations at an all-time high, raising the call for education reform on all levels.

“The policies we have right now are resulting in extreme levels of student stress, parent stress, and teacher stress,” Mr. Larson said.

“It doesn’t have to be this way. But people have to be bold enough,” Mr. Mac said. “Should we be meeting in classrooms like this? Should we really have these big campuses? Is that really the best way?”

Building off of this, Mr. Mac believes this aspiration towards envisioning new ways to educate students is founded in the Lasallian tradition. “One of the things we pride ourselves on as a Lasallian institution is St. John Baptist de La Salle revolutionized education in his time. We’re still doing it in many ways the same way it was done in the 1700s. Why?”

Additional reporting for this piece was contributed by Staff Reporter Noemi Skovierova.