What You Need To Know About the Emerging Coronavirus Variants

Variants are caused by small copying errors called mutations in the genome of a virus. The C.D.C. is currently monitoring three variants that are spreading globally.

February 3, 2021

With the coronavirus pandemic still raging in the United States and Oregon case numbers averaging around 660 new infections each day, several variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus have emerged in the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Brazil, all of which have already been identified in the U.S.

Even as around 1.3 million people in the U.S. are inoculated with the coronavirus vaccine each day, experts say that the variants — one of which is suspected to be about 50 percent more transmissible than the original COVID-19 strand — could prove extremely troubling as they continue to spread across the country.

With many La Salle students and staff transitioning to hybrid learning, the emergence of these new variants means that mask-wearing and social distancing practices are of even greater importance.

Here’s what you need to know about the newly-circulating COVID-19 variants.

What are the variants?

“As viruses replicate, small copying errors known as mutations naturally arise in their genomes,” according to a recent New York Times article. “A lineage of coronaviruses will typically accumulate one or two random mutations each month.”

While most of these mutations have no effect on the behavior of the virus, every once in a while, a mutation will arise that allows the virus to survive and reproduce more effectively.

Since the coronavirus was first identified in Wuhan, China in December of 2019, there have been more than 100 million documented cases worldwide. Each new infection of the coronavirus provides an additional opportunity for the virus to mutate and form variants.

Where have the variants emerged, and how are they different from the original strain of coronavirus?

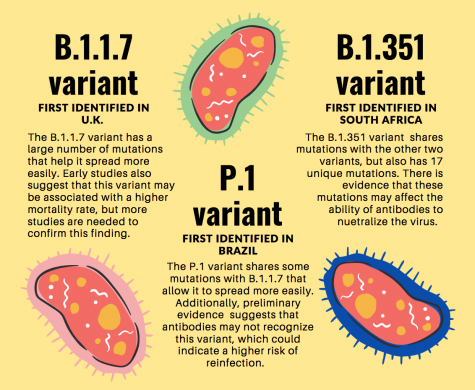

The C.D.C. has noted three variants of SARS-CoV-2 that are spreading globally right now.

The first of these is known as the B.1.1.7 variant, and was originally detected in the U.K. in September of 2020. This variant, which was named a “variant of concern” by the C.D.C., has an unusually high number of mutations on its spike proteins, which are the parts of the virus that bind it to a cell.

Based on a study from British scientists that is currently under peer review, the B.1.1.7 variant is around 50 percent more transmissible than the coronavirus that was first documented in Wuhan, and may be associated with a slightly higher degree of mortality as well. So far, the B.1.1.7 strand has been identified in at least 20 U.S. states, including Oregon.

Because of its ability to spread more easily, the C.D.C. has predicted that this strain of the coronavirus could become the dominant source of infection in the U.S. by March.

Currently, there are at least four known cases of the B.1.1.7 variant in Oregon. However, the first two patients had no known travel history, suggesting that the virus is likely circulating within the state.

A different variant was detected in South Africa in early October of 2020, and has been labeled B.1.351. The South Africa variant shares some similarities to the U.K. strain, and likewise, appears to be more transmissible.

However, the B.1.351 strain may also be more resistant to antibody therapies. This means that the antibodies that are developed after contracting the virus or being vaccinated with the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine may not be as effective in preventing reinfection. In one trial conducted by Novavax, a company making vaccines for the U.S., the B.1.351 variant infected many trial participants even after they had already had COVID-19.

The first cases of the B.1.351 variant in the U.S. were identified in two people in South Carolina on Thursday, Jan. 28. Neither of the people infected had any travel history.

The third variant noted by the C.D.C. is the P.1 strain, which was first detected in Brazil last month, but may have been circulating there as early as July 2020, according to sequencing studies.

Like the other two variants, P.1 has mutations on its spike protein and is suspected to be more transmissible. Early evidence also suggests that antibodies might not recognize the P.1 variant, which could indicate a higher risk of reinfection, mirroring the risks of the South Africa variant.

The first case of the P.1 variant in the U.S. was identified on Monday, Jan. 24 in Minnesota. This variant has also spread to Peru, Germany, South Korea, and Japan, among other places, but there are currently no known cases in Oregon.

Another variant has not been noted by the C.D.C. as a globally-spreading variant, but has grown to account for a large number of cases in California, particularly in Los Angeles and the Bay Area. This California variant, also called CAL.20C, is not known to be more contagious than the original strand of coronavirus, but has already been detected in Oregon in Washington, Yamhill, and Multnomah counties.

How are the emerging variants expected to impact vaccines?

Biotechnology companies Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech confirmed that their vaccines appear to be effective against the U.K. and South Africa variants, and there is no evidence to suggest that vaccines won’t work against the Brazil variant.

However, the companies noted that their vaccines might offer less protection against the South Africa variant. Since the Brazil strain resembles the South Africa one, scientists expect that it will behave similarly, though the drug companies do not yet have data on this variant.

Another drug company, Johnson & Johnson, recently announced the development of a single-dose vaccine for COVID-19, which was found to provide strong protection against the virus. But, similar to the findings of Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, this vaccine’s efficacy rate was found to be significantly lower in South Africa, where the B.1.351 variant accounts for most cases. A different vaccine made by Novavax was also found to be less effective against the South Africa variant.

However, experts have warned against assuming that a decrease in neutralizing ability, like the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines displayed, means the vaccines are ineffective against new variants.

This is because of a “cushion effect” that vaccines have, said Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the government’s leading expert on infectious diseases and President Biden’s chief medical adviser on the coronavirus. The current vaccines provoke such a powerful immune response that they will continue to be effective even with a reduction in antibody strength.

Even so, as a safety precaution, Moderna has begun the development of a new form of their vaccine to be used as a booster shot against the variant in South Africa, acting like an “insurance policy,” said Dr. Tal Zaks, Moderna’s chief medical officer in an interview with the New York Times.

This vaccine will hopefully be able to be formulated much faster than earlier vaccines, thanks to the mRNA technology used in both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.

For now, experts say that the challenge will be vaccinating as many people as possible to prevent new variants from developing.

Scientists said the U.K. variant (B.1.1.7) has the potential to erupt in the U.S. in the next few weeks, creating new pressures for already-overwhelmed hospitals.

In addition, the ubiquity of the virus is what has caused mutations to evolve sooner than expected. If the virus continues to spread, new mutations could continue to occur at a faster rate.

Although the vaccine rollout has picked up pace in the U.S., there are many countries where no one has been vaccinated.

Experts have warned that new variants could develop in other parts of the world that would make the virus resistant to the vaccines. For this reason, scientists emphasize that it is in everyone’s best interest to vaccinate the world as quickly as possible.

What can you do to protect yourself and others from the variants?

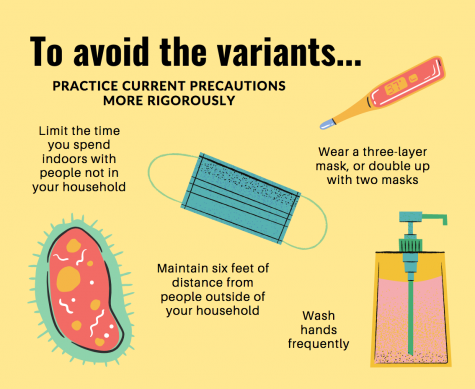

To avoid the variants of the coronavirus, scientists advised people to double down on current precautions, like mask wearing and social distancing. Being even more rigorous with these practices could help protect from the more transmissible variants.

According to Linsey Marr, an engineering professor at Virginia Tech and an expert on the airborne transmission of viruses, the best mask to wear is one with three layers: two layers of cloth and a filter in between the cloth. If you don’t have a mask that fits these requirements, an alternative option is to wear two masks at once for extra protection against more dangerous variants.

Mary Sawyers, a spokeswoman for Washington County Public Health in Oregon, reinforced the idea that the variants simply provide “another reason to keep doing what we’ve been doing,” she said. “Wearing masks, wearing masks, wearing masks, and keeping our distance until a large majority of us are vaccinated.”

Another strategy Dr. Marr emphasized is to continue limiting contact with those outside of your household as much as possible. This includes avoiding crowds, reducing the time you spend indoors with people not in your household, and keeping at least six feet of distance at all times.

Ultimately, the best way to reduce the risk of contracting the coronavirus and its variants is to get the vaccine. But, until this is possible, scientists advise reducing exposure to other people and practicing current precautions more exhaustively.

“I think there is no room for error or sloppiness in following precautions, whereas before, we might have been able to get away with letting one slide,” Dr. Marr said.